Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

The Meaning of Rotational Inertia

If you apply a net force on an object, it will accelerate. We saw back in Newton's Laws, however, that not all objects have the same acceleration even though they were pushed with the same net force. You might recall that more massive objects have a smaller acceleration. We explained this in terms of inertia—the tendency of an object to resist a change in motion. All objects possess inertia, but not all objects have the same amount. In fact, mass is the way we measure how much inertia an object has.

Throughout this chapter, we have discovered a rotational quantity that is associated with many of the linear quantities explored in earlier chapters. Is there a rotational counterpart to inertia as well? Yes, it’s called rotational inertia. Clever, huh!? Rotational inertia is the tendency of an object to resist a change in rotational motion. We saw earlier in this lesson that when a torque is applied to an object, it causes the object to rotate. More specifically, it causes an angular acceleration. But not all objects experience the same angular acceleration when a torque is applied. What determines the size of the angular acceleration for a given torque? The rotational inertia does.

Just like mass was the way we measured the inertia of an object, the moment of inertia is the way we measure the rotational inertia of an object.

So, what determines the rotational inertia of an object? Just like inertia for translational motion, rotational inertia depends on mass. A massive stone potter’s wheel is hard to get spinning. And once it is moving, it has a real tendency to stay in motion. But unlike inertia for translational motion, rotational inertia also depends on where the mass is located in relation to the axis of rotation. You might consider, for example, weights on a bar. Put the weights close to your hands, and it’s much easier to rotate them back and forth than when those same weights are at the ends of the bar. Both arrangements have the same mass, but where the mass is located matters. Rotational inertia depends on how far the mass is from the axis of rotation.

Maybe you’ve watched a gymnast pull her body into a tuck position when she rotates. She does this because decreasing her rotational inertia means it is easier to start rotating.

Calculating Moment of Inertia for Point Masses

So how do we quantify the rotational inertia of an object? We do so by calculating its moment of inertia. We’ll use the letter I to represent moment of inertia. If the object can be considered as a collection of point masses, we find its moment of inertia by calculating the sum of the masses times their distance from the axis of rotation squared.

If you think back to our weights on a bar example, this equation makes sense. The smaller r is, the smaller the moment of inertia and the easier it is to get the object rotating. You might also be able to imagine why a tightrope walker at the circus holds a really long bar that is weighted on each end. A bar with a large moment of inertia decreases his tendency to rotate.

Example 1: Comparing Moments of Inertia

Problem: A lab group has a long but very thin stick and two 0.50 kg balls of clay. One student puts the two balls of clay 10 cm from the middle. The other student puts the clay balls 40 cm from the center. If we approximate the stick as massless and the balls of clay as point masses, what is the moment of inertia for each configuration?

Solution: Since the stick can be considered massless, we only have two masses that contribute to the moment of inertia calculation. The moment of inertia in (a) is 0.01 kg·m2; the moment of inertia in (b) is 0.16 kg·m2. It is interesting to note that by putting the clay balls at 40 cm from the axis instead of 10 cm, the moment of inertia has increased by 16 times.

Example 2: Axis Location Matters

Problem: A rectangle is formed by joining four large masses at its corners. Each mass (m = 8 kg) is joined by a very light rod of negligible mass. Find the moment of inertia of the rectangle if its axis of rotation is (a) the x-axis, and (b) the y-axis

Solution: For this example, we have four masses. We measure the distance to each mass from the axis of rotation. Doing so, we find the moment of inertia about the (a) x-axis is 3200 kg·m2, and about the (b) y-axis is 800 kg·m2. The same system of masses will have a different moment of inertia depending on the axis of rotation.

Like mass, moment of inertia is a scalar. Since we square the distance from the axis of rotation to the mass, it doesn’t matter what direction the mass is from the axis.

Determining Moment of Inertia for Continuous Masses

Most objects, however, aren’t point masses connected by a massless rod. So, how do we find the moment of inertia of a continuous object? To answer this question, let’s consider a ring with an axis through the center and its mass spread evenly around the rim. What physicists do is think of the ring as a collection of 'point masses' by breaking the ring into really small pieces that are essentially points, and then apply the same equation as we did above. While we would ideally break the ring into an infinite number of point masses (if they are truly to be points), we will approximate by breaking this ring into 32 'point masses' that are all a distance R from the axis. By doing so, we’ll get an idea of what is actually done for such a calculation. Since the distance from the axis to each of these masses is the same, we can factor out the R2 from every term in the summation. Then, adding up all the masses will simply give us the total mass of the whole ring. Thus, the moment of inertia for a ring with its axis through the center is simply M R2.

Physicists have gone through this same process for other commonly shaped objects that might be rotated and have come up with an expression for the moment of inertia for each. Deriving the moment of inertia equation for most of these is trickier than the ring, however, since the distance each 'point mass' is from the axis of rotation varies. As such, those who derived these equations used calculus to help them. We sure don’t need calculus to use these results, however. As we do, we will see that these results can help us explain some pretty interesting things about rotating objects.

Let’s remind ourselves what the moment of inertia tells us. A big moment of inertia means that it is more difficult to get that object rotating compared to an object with a smaller moment of inertia. A big moment of inertia also means it is more difficult to stop it from rotating once in motion. Let’s apply this concept and these equations to predict the motion of these objects.

Example 3: The "Speeding Down Hill Race"

Problem: Four objects (a disk, a ring, a solid sphere, and a hollow sphere) are going to race down a hill. Each has the same radius, and each has the same mass. Rank these from quickest to slowest in their downhill race to the finish line.

Solution: See below to see the race in action. Did you notice that for those that have a greater percentage of their mass further from the center, it was more difficult to begin rotating? The ring, for example, has all its mass far from the center. Compare that to the solid sphere, which has most of its mass closer to the center. Did you also notice that the coefficients in the moment of inertia equations help us predict their ranking?!

That’s why we call this the Speeding Down Hill Race!

Example 4: Calculating Moment of Inertia for a Rod Around Two Axes

Problem: A rod has a mass of 850 grams and length 60.0 cm. What is its moment of inertia when rotated about (a) its center of mass, (b) its end? (c) Given these values, why does it make sense that it is ‘harder’ to get the rod rotating about an axis through its end compared to its center of mass?

Solution: (a) Typically, we will convert masses to kilograms and lengths to meters so that we can compare moments of inertia in units of kg·m2. Doing so, gives ICM = 0.0255 kg·m2. (b) Iend = 0.102 kg·m2. (c) This makes sense since more mass is further from the axis of rotation when pivoted about its end.

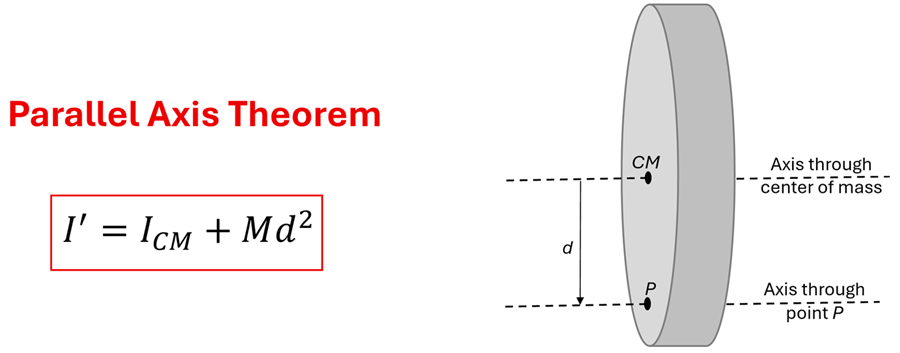

Axis Matter

We noticed from Example 4 that the same object (a rod) has a significantly different moment of inertia depending on the axis of rotation. We can't, for example, just give a single equation for the moment of inertia is for a rod. The axis matters. But since we could rotate any of the above objects around many different axes, wouldn’t it be nice if there was a quick way to get the moment of inertia about another axis if we just knew how far away the axis was shifted from the center? Good news, there is! We call it the parallel axis theorem. We can find the moment of inertia about any axis (as long as it is parallel) by just knowing the moment of inertia through its center of mass and how far away the new axis is.

In this equation, I' is the new moment of inertia when rotated about the new axis through point P. As this equation suggests, rotating an object about an axis through its center of mass has the smallest moment of inertia of any axis. This makes sense because, on average, the mass is closest to the axis of rotation when rotated about its center.

Example 5: Using the Parallel Axis Theorem

Problem: When a rod is pivoted about its center, its moment of inertia is 1/12 ML2. Use the parallel axis theorem to show that the moment of inertia of this same rod pivoted about its end is 1/3 ML2.

Solution: Applying the parallel axis theorem, we recognize that d = L/2. After simplifying, we are able to show how the moment of inertia of a rod pivoted about an axis through its end is indeed 1/3 ML2.

In this lesson, we’ve explored the concept of rotational inertia, the tendency of an object to resist a change in its rotational motion. We saw that an object's rotational inertia depends on its mass and how far the mass is located from the axis of rotation. For a given axis, each object has a moment of inertia, which is how we quantify the object’s rotational inertia.

You might be asking, "What is knowing an object’s moment of inertia good for anyway? Do we actually use these in real life?" You bet we do! Let’s pull together all we learned about rotational motion thus far in order to understand Newton's Second Law for Rotational Motion. That is where we are going next.

Check Your Understanding

Use the following questions to assess your understanding. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

1: Rotating a pencil about each of the three axes shown yields three different rotational inertia values. Using the numbered axes, rank their rotational inertia from smallest to largest.

2: When a spinning figure skater pulls her legs and arms inward, she spins faster. What does pulling her body inward do to her rotational inertia?

3: Four 'massless' rods each rotate about the same axis on their left end. Various masses are attached to the rods as shown. Ranks the four rod-mass systems from smallest to greatest rotational inertia.

4: A bowling ball has a mass of 7.26 kg and a diameter of 21.6 cm. Assuming the bowling ball is a uniform solid sphere, calculate the moment of inertia for this ball as it spins about an axis through its center of mass.

5: The figure shows a top view of a uniform disk with three holes drilled through it. The disk is allowed to rotate along an axis through any of these holes. Which axis will offer the greatest rotational inertia and why?

6: A hula hoop (which can be considered a ring) has a radius of 0.40 meters and a mass of 0.25 kg. Find the moment of inertia if it is rotated about an axis:

(A) through it's center of mass

(B) about a point on its rim

Looking for additional practice? Check out the CalcPad for additional practice problems (Sets 1-4).

Created with modified Wikimedia commons (From Gan Khoon Lay) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Icon-angry-hand-4230419.svg under license Creative Commons

Borrowed from Wikimedia commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rolling_Racers_-_Moment_of_inertia.gif

Created with modified Wikimedia commons (From Blake Thompson) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Icon-pencil-9576.svg under license Creative Commons