Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Maintaining ‘Status Quo’

In the previous section, we explored the significance of Faraday’s Law. We saw that a change in magnetic flux through a loop of wire induces an electromotive force (or emf) which in turn causes a current in the loop. While Faraday’s Law helps us calculate the magnitude of the induced emf, we need another law to help us understand the direction of the induced emf. Lenz’s Law will do just that.

Image a loop of wire and a bar magnet as shown in the figure to the left. There is a flux through the loop as we can see some of the B-field lines piercing the area enclosed by the loop. This, however, does not induce an emf in the loop. We saw in the last section that we need a changing flux to do that.

Imagine next that we are moving the north end of the bar magnet toward the loop as shown in the figure to the right. We see now that there is not only a flux through the wire loop, but that there is an increasing flux since the number of B-field lines that pierce the area enclosed by the loop has gotten larger with time.

You’ll notice that in the case of the changing flux there is a current induced in the wire. To account for the direction of the current we’ll need to understand Lenz’s Law. Lenz’s Law states:

the induced emf (and thus the induced current) will be in a direction such that its magnetic field opposes the change in flux.

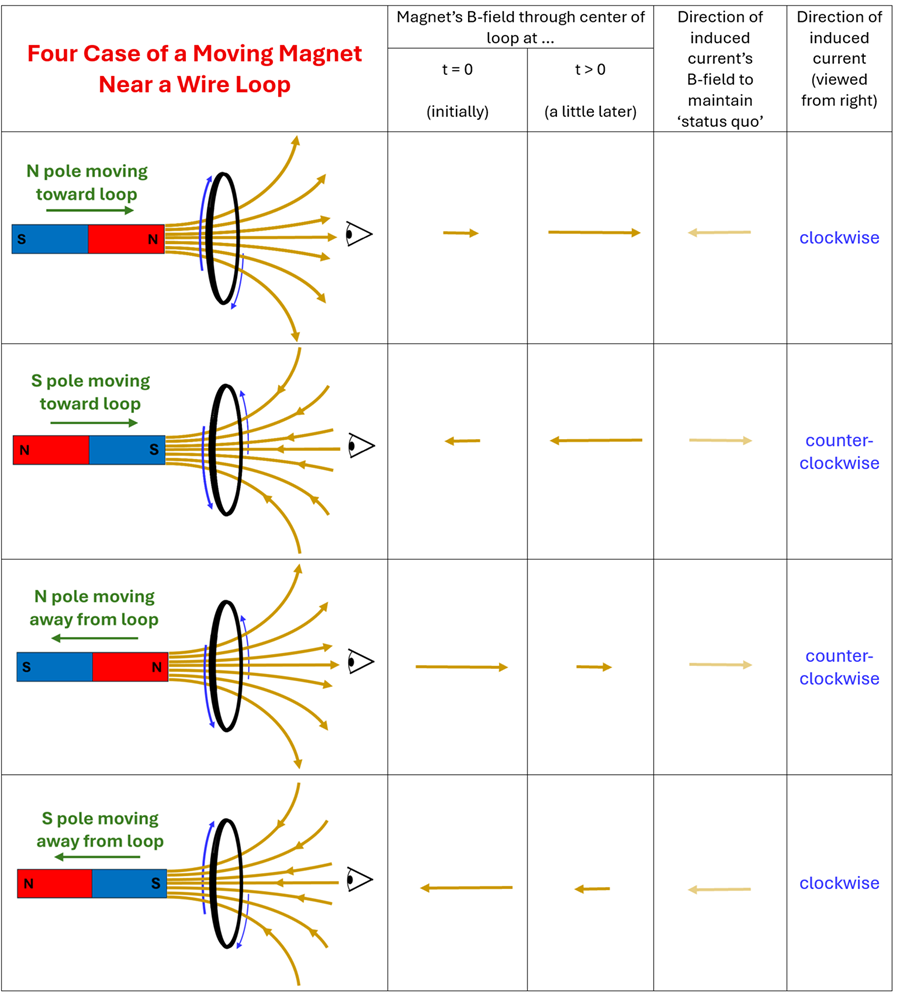

For the case on the right, we see that a current is induced in the clockwise direction when viewed by the observer from the right. Lenz’s Law suggests that the current must point in this direction because the magnetic field created by the induced current will point to the left to oppose the increase in the rightward pointing magnetic field from the bar magnet. In other words, the magnetic field created by the induced current wants to cancel out the increase in the rightward B-field. It’s important to note that the induced current’s B-field doesn’t always opposes the direction of the bar magnet’s B-field but instead always opposes the change. To help us wrap our heads around this, let’s consider the four cases below.

A person who doesn’t like change likes to keep the ‘status quo.’ That is, they like to see that things continue in whatever direction they are going. The induced current is like that, too. It wants to maintain status quo. It does this by creating its own B-field to try to keep the flux as constant as possible.

Let’s consider two examples in which we apply Lenz’s Law to predict the direction of the induced emf--which will be the same direction as the induced current.

Example 1: A Loop with an Increasing Flux

Problem: A loop of wire is immersed in a magnetic field that points into the page as shown. The strength of the magnetic field is increasing with time. Predict the direction of current induced in the loop.

Solution: Lenz’s Law tells us that the induced current will be in a direction such that its magnetic field opposes the change in flux. We can see that the magnetic field points into the page and is increasing. Thus, the flux is increasing with time. Since the induced current will seek to maintain status quo, it will create a B-field pointing out of the page for the region inside the loop where the flux is increasing. Using the Field-finding Right Hand Rule, we can see that the induced current will be in the counterclockwise direction around the loop since, when our right thumb points in that direction our fingers will curl around the wire and be pointing out of the page in the area inside the loop.

It’s important to remember that the magnetic field created by the induced current doesn’t always point opposite the direction of the external changing magnetic field. The induced field is in the opposite direction in this example only because the flux is increasing. Let’s investigate a second example where the flux is decreasing. Here we’ll see that the induced current’s B-field will be in the same direction as the external field as it tries to maintain status quo.

Example 2: Motional EMF in a Loop with Decreasing Flux

Problem: Consider a situation that we explored in the previous section where a conducting bar is allowed to slide along two parallel rails connected by a resistor R. The entire set-up is immersed in a uniform and constant magnetic field. Imagine the conducting bar is being pushed to the left and is moving in a direction such that the area enclosed by the closed conducting loop is decreasing with time. Predict the direction of the induced current in the closed loop.

Solution: As the conducting bar moves left, we see that the area enclosed by the closed loop is decreasing. Since the B-field is constant but the area is decreasing, the flux is decreasing. Lenz’s Law states that the induced current will be in a direction such that its magnetic field opposes this change in flux. The current will point in a counterclockwise direction in order to create its own magnetic field that will add to the existing field to try to maintain the magnetic flux.

The figure above shows an added magnetic field that points out of the page next to each of the hands illustrating the Field-finding Right Hand Rule. Obviously, the added field is not limited to these two locations but actually permeates the entire region inside the loop. These two dots next to the hands are merely meant to illustrate how the induced current’s field adds to the existing field in the case where the flux is decreasing.

Magnetic Force & Conservation of Energy

As a thoughtful physics student, you might be wondering, “Why does the induced current want to maintain a status quo flux?” After all, how does it ‘know’ the direction of the B-field and whether the flux is increasing or decreasing? It turns out that Lenz’s Law is a result of the magnetic force and the conservation of energy.

Let’s investigate Example 2 above just a little deeper. Let’s imagine a microscopic view of a plus charge and a minus charge within the conduct bar. As the conducting bar is pulled to the left, both of these charges will be moving leftward. Since these charges are in a magnetic field pointing out of the page, they each feel a magnetic force. The plus charge feels a force toward the top of the page as described by the Force-finding Right Hand Rule; the minus charge feels a force toward the bottom of the page as described by the Force-finding Left Hand Rule. This separation of charges inside the moving bar creates a potential difference in much the same way that a battery does. This is why there is an induced emf in this loop acting as if there was a battery present!

But wait, it gets even better! As the current flows counterclockwise around the closed loop, it travels toward the top of the page through the conducting bar. According to the Force-finding Right Hand Rule for current, a conducting bar that carries current toward the top of the page in a magnetic field pointing out of the page feels a rightward magnetic force. Therefore, the only way to keep the conducting bar moving leftward at a constant velocity is for someone to exert a force. This person does work on the bar. But where does the energy go when this work is done on the conducting bar? By conservation of energy, it must go somewhere, right? It goes into creating the emf which causes the current in our loop! In other words, our mechanical work (pulling the bar leftward) generates electricity (the induced current). You’ve just discovered the world’s simplest generator!

Putting it All Together

Before we wrap up this lesson, let’s review all that we’ve learned. We’ve seen that a changing magnetic flux is necessary to induce an emf—and thus a current—in a wire loop. The magnitude of this induced emf is determined by Faraday’s Law. The direction of this induced emf (and induced current) is described Lenz’s Law. We also know that don’t get something for nothing. There is a 'cost' to generating this electrical energy. The 'price' we pay is doing work by mechanically exerting a force over some distance to cause this change in magnetic flux. In a nutshell, this is what causes electromagnetic induction.

Let’s see if we can put this all together by considering the examples below.

Example 3: Applying Faraday's Law and Lenz's Law

Problem: A long, straight wire has a current that is decreases with time. As a result, the magnetic field at the location of a distant rectangular loop (total resistance = 2.0 Ω) made of 12 turns of wire decreases from 0.95 T to 0.35 T over 0.30 seconds. (Assume that the magnetic field is nearly uniform across this rectangular loop at any moment in time.) Determine the magnitude and direction of the current induced in the rectangular loop.

Solution: Applying the Field-finding Right Hand Rule, we see that in the vicinity of the rectangular loop the magnetic field created by the long, straight wire points out of the page. Since the magnetic field inside the loop is points out of the page and is decreasing, Lenz’s Law suggests that the induced current will point counterclockwise. Applying Faraday’s Law and Ohm’s Law, we find the induced current in the rectangular loop to be 1.8 Amps.

Example 4: Moving Square Loop Revisited

Problem: Let’s consider the situation we’ve encountered earlier in this lesson. A square (20.0 cm x 20.0 cm) loop of wire is caused to move rightward at a constant velocity of 30.0 cm/s in a magnetic field of 0.40 T as shown. The wire loop has a resistance of 0.80 Ω. Determine (a) during what intervals of time a current is induced in the wire, (b) the magnitude of this induced current, and (c) its direction.

Solution: (a) By Faraday’s Law, a change in flux is needed to induce current in the loop. Since the magnetic flux through the loop is changing from 0 to 2 seconds and from 3 to 5 seconds, it is during these two time intervals that a current will be induced in the wire. (b) To find the magnitude of this induced current, we’ll use Faraday’s Law in conjunction with Ohm’s Law. Doing so, we find the induced current to be 0.030 Amps. (c) From 0 to 2 seconds, we see that the flux is increasing. Lenz’s Law says that the induced current will be in a direction such that its magnetic field opposes this increase in flux. By using the Field-finding Right Hand Rule, we see the at induced current will travel counterclockwise around the loop from 0 to 2 seconds. From 3 to 5 seconds, we see that the flux is decreasing. In order to maintain status quo, Lenz’s Law suggests that the induced current will now travel clockwise around the loop since this current will produce a magnetic field inside the loop that points into the page in an effort to maintain the flux.

In this lesson we’ve explored how a changing magnetic flux induces and emf and current in a loop of wire even without a battery. Faraday likely had no idea the breadth of applications that would come as a result of this discovery. Our next lesson will explore some of these real-life applications of electromagnetic induction including how electricity is actually generated and how it is transmitted to your home. Like Faraday, perhaps this lesson has generated additional questions in your mind. Perhaps you see the power of this discovery and how it has and will likely continue to revolutionize our world. If so, you’re in good company. Uncovering a couple of these applications is where we’re headed next.

Check Your Understanding

Use the following questions to assess your understanding. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

1. A single rectangular loop of wire is placed in a B-field as shown. The magnetic field increases from 0.10 T to 0.40 T in 0.20 seconds.

(A) Determine the direction of the induced emf in this loop.

(B) Determine the magntiude of the average induced emf in this loop.

2. A magnetic field pointing into the page increases with time according to the equation B(t) = 0.20 Tesla + (0.1Tesla/sec) t from 0 to 5 seconds. A circle loop of wire of radius 0.30 m and a resistance/length rating of 0.15 Ω/m is in this magnetic field as shown.

(A) Determine the magnitude and direction of the induced emf.

(B) Determine the magnitude and direction of the induced current in the loop.

3. Four identical wire loops lie in the same plane next to a long, straight wire that is carrying current as shown. The current in the long, straight wire is suddenly increased.

(A) What is the direction of the induced current in each loop?

(B) Rank these four loops from least induced current to greatest.

4. A U-shaped wire of negligible resistance is placed vertically in a magnetic field as shown. A crossbar with resistance R slides over each side of the wire and completes a conductive loop. As the crossbar falls due to its weight, current is generated in the conductive loop.

(A) What is the direction of the current induced in the crossbar when it is falling with velocity v?

(B) What is the magnitude of the induced current at this moment?

(C) Since there is an induced current in the moving crossbar, it will 'feel' a magnetic force. Use the Force-finding Right Hand Rule to determine the direction of the magnetic force on the crossbar as it falls.

5. A common demonstration of Lenz’s Law is performed by dropping a neodymium magnet down a hollow copper pipe as shown. Rather than continuing to accelerate, the magnet quickly reaches terminal velocity as it falls. Assuming the magnet is oriented with its north pole at the bottom:

(A) What is the direction of the current induced in the yellow ring (which is merely a colored portion of the copper pipe) when viewed from above?

(B) What is the direction of the magnetic field created inside the yellow ring due to the current induced in this portion of the pipe?

(C) Using your answer to (B), explain why the magnet reaches terminal velocity rather than continuing to accelerate as it falls.

We Would Like to Suggest ...

Sometimes it isn't enough to just read about it, you need additional practice. Check out the CalcPad for additional practice problems.

Images are author-created except hands borrowed from Wikimedia Commons (From P.Sumanth Naik) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Direction_of_field.png under license Creative Commons