Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Matter Revisited

In the previous section, we defined matter as anything that has mass and volume. To be classified as matter, there are two requirements:

Mass: there has to be some stuff in the object.

Volume: the stuff has to occupy some space.

Mass and volume. Stuff and space. Scientists are often interested in how much stuff fits into a given space. In other words, we’re interested in the concentration of the mass in a given amount of volume. Physicists call this idea density. That’s the focus of this section.

Density Concept

Density is a physical property of a material. While matter in any state (solids, liquids, or gases) has a density, we are especially interested in the density of liquids and gases in this lesson since liquids and gases are fluids—and that is what this whole chapter is about.

Density is closely tied to mass and volume. The concept of density provides a measure of how concentrated mass is in a given amount of space. A relatively dense object has a relatively large amount of stuff in its space. A less dense object has a relatively small amount of stuff in its space. If you prefer the more technical language, simply exchange the word mass for stuff and volume for space. Density is the ratio of the mass to the volume. Let’s conduct two thought experiments in order to make sense of this concept.

Thought Experiment #1

Consider a beaker sitting on a balance. Beakers can be used to measure space—they can be used to measure volume. And while there are more accurate tools in the laboratory to measure volume (such as a graduated cylinder), a beaker can provide at least an approximate value for volume. Balances can be used to measure stuff—they measure mass. Some balances can measure very accurately; they can measure to the thousandth of a gram or even better. For our purposes, we’ll just use an ordinary balance that measures to the nearest gram.

In the left picture below, we see that the mass of the empty beaker is 100 g (grams).

Now consider the next picture, case A. Let’s say a fluid is poured into this beaker up to the 100 mL (milliliter) line. We would say the volume of this liquid is 100 mL. That’s the space that this liquid takes up. We also notice that the balance now reads 200 g. Since we recognized that the empty beaker had a mass of 100 g, can you determine the mass of the liquid that was added in this case? Right! 100 g. The fluid’s mass is the total mass of the beaker and fluid minus the mass of the beaker.

Fluid Mass = Total Mass - Mass of Beaker

In case B, we’ve added more of the same fluid. Now the mass of the fluid is 200 g and its volume is 200 mL. In case C, we’ve added still more of this same fluid. In this case, the mass of this fluid is 300 g and its volume is 300 mL.

The mass of the fluid in case A is less than the mass of the fluid in case B, which is less than the mass in case C. It is also true that the volume of the fluid in case A is less than the volume of the fluid in case B, which is less than the volume in case C. But there is something that is the same for all three cases. Can you recognize what it is?

The ratio of the mass to the volume in each case is identical. In other words,

We give a name to this ratio of mass to volume. We call it density. Density = mass / volume. The fluid in cases A, B, and C all have a density of 1 g/mL.

Physicists often use the Greek letter ρ (pronounced ‘rho’) to represent density. Chemists sometimes use the letter D to represent density. Both ρ and D represent the same quantity. However, since we use D in other chapters to represent distance or displacement, we’ll use the variable ρ to represent density in this chapter.

Look back at Thought Experiment #1. It is important to note that, since we used the same fluid in each case, the density is the same. This is super important in that it gives us a way to identify this particular fluid. As we’ll see, each unique fluid has its own density. This is one way we can tell one fluid from another even though they may look quite similar.

That brings us to Thought Experiment #2, where we’ll consider the density of different fluids.

Thought Experiment #2

Consider once again a beaker sitting on a balance. As in Thought Experiment #1, we see that the mass of the empty beaker is 100 g. This time, cases A, B, and C all have 300 mL of a fluid poured into the beaker. Thus, the volume of each fluid is the same. The masses of the fluids, however, are different. Once again, to get the mass of the fluid, we needed to subtract off the mass of the beaker itself.

We can now use our density equation to find the density of each of these three different fluids. What is important here is that these are different types of fluids, so each of these has a different density.

What we discover in Thought Experiment #1 is that no matter what volume of a single fluid we choose, the density of that fluid will be the same. What we discovered in Thought Experiment #2 is that different fluids will have different densities.

Part of the power of a density calculation is that it can help us identify the fluid that is being used. By comparing our own calculated density to that of known densities that we can find online or in tables like the one below, we can determine what an unknown fluid might be.

| Substance |

State |

Density (g/mL) |

| Helium* |

Gas |

0.000179 |

| Carbon Monoxide* |

Gas |

0.00114 |

| Air (dry)* |

Gas |

0.00123 |

| Gasoline** |

Liquid |

0.66 - 0.77 |

| Rubbing Alcohol |

Liquid |

0.92 |

| Water |

Liquid |

1.00 |

| Maple Syrup |

Liquid |

1.33 |

| Mercury |

Liquid |

13.6 |

* at 25° C and 1 atm. (Gas densities depend on pressure and temperature)

** Varies with composition and temperature |

Let’s see how this works in Example 1 below, where we try to determine what fluids were used in Thought Experiment #2.

Example 1: Identifying Unknown Fluids

Problem: Using the results from Thought Experiment #2 above, identify what fluid A, fluid B, and fluid C might be.

Solution: Fluid A is likely gasoline. According to the table, its density is in the range of that of gasoline (0.66 – 0.77 g/mL). Similarly, Fluid B is likely water. The table shows that the density of water is 1.00 g/mL. Fluid C is likely maple syrup. We can see that its density is approximately 1.33 g/mL.

Example 2: Finding a Mystery Fluid

Problem: A clear liquid was found in an unlabeled container at a crime scene. Forensic scientists need to determine what the liquid is. One method they chose to use is to find its density. They measured out 100 mL of liquid and found that it had a mass of 92 grams. Using the table above, what liquid might this be?

Solution: The liquid may be rubbing alcohol. We find that the density of the clear liquid is 0.92 g/mL. Using the table above, this corresponds to rubbing alcohol.

In reality, identifying an unknown fluid using its density is more challenging than we’ve made it out to be. While our table of densities above lists a few fluids, there are thousands of fluids, and many of them have densities that are quite similar. Nonetheless, finding the density of a fluid is one way to help identify what it might be.

Using the Density Equation

While solving for the density of a fluid is valuable in identifying the type of fluid, there are times when we might know what the fluid is and instead want to determine its mass or volume, where measuring these quantities might be difficult.

The density equation has three variables in it—ρ, m, and V. If the value of any two of these three variables is known, the value of the third variable can be determined. The given formla is set up so as to solve for the density of a fluid from our knowledge of the fluid’s mass and volume. But what if we know what fluid it is (and thus know its density), and wish to solve for its mass or volume? For those who are believers in algebra, that’s not a problem at all. The equation can be manipulated to find its mass or volume. The derivation below shows how to algebraically manipulate ρ = m/V to obtain an m = … equation.

The final need is to get a V = … equation. The derivation below shows how to algebraically manipulate ρ = m/V to obtain a V = … equation.

We have now used the density equation to generate formulas that allow us to solve for density, mass, and volume.

Let’s try an example where we will need to solve for an unknown mass and one where we solve for an unknown volume.

Example 3: Finding the Mass without a Balance

Problem: What is the mass of 200 mL of mercury? Use the table of densities above.

Solution: As we’ve done before, let’s list our knowns and unknowns. This helps us identify the form of the equation that we’ll want to use. After plugging in numbers and canceling some units, we find the mass is 2720 grams. As one of the densest liquids, such a small volume of mercury has a significant mass.

Example 4: Is it Full?

Problem: Pure maple syrup comes in a plastic jug. By filling an empty jug with water, you find that the container can hold exactly 1000 mL when completely full. At the grocery store, you find an identical container of pure maple syrup. The manufacturer says the net mass (mass of syrup only) is 1100 grams. Is the container completely full?

Solution: No, the container only holds 827 mL of syrup when it could hold 1000 mL. The container is only 82.7% full.

Keeping Units Straight

Throughout this chapter, we’ll see that needing to find and then use the density of a fluid will come up time and time again. As such, it is important that we have a good grasp of this concept. We’ll also discover that the quantities of mass, volume, and density can have different units. Mass, for example, can be measured in grams (g) or kilograms (kg). Volume, however, can be measured in everything from milliliters (mL) to liters (L) to cubic centimeters (cm3) to cubic meters (m3). We’ll want to get comfortable with converting any one of these volume measurements to the others. We’ll find that one of the handiest volume conversions to know is that 1 mL = 1 cm³. Imagine, for example, you had a graduated cylinder filled with 1 mL of a fluid. If you pour this into a cube that is 1 cm x 1 cm x 1 cm, it would exactly fill it.

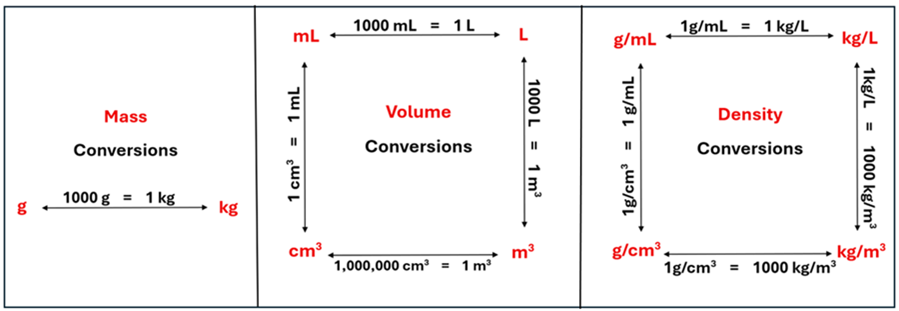

Since mass and volume can take on different units, it follows that density can take on units such as g/mL, kg/L, g/cm3, or kg/m3. Being able to convert between these units will be important as well. How do we keep these conversions straight? The chart below may be helpful as we perform calculations involving mass, volume, and density with different units.

How does this chart work? Start with the units (shown in red) on the quantity that you know. Next, identify the units (again in red) to which you want to convert that value. Between these two red units is a conversion factor (shown in black). The conversion factor is a multiplying factor of two quantities that are equal. Since they are equal, we can write them as a fraction by putting one in the numerator (the upstairs part) and the other in the denominator (the downstairs part). How do you know which goes in the numerator and which goes in the denominator? Let’s look at a mass example to illustrate this. Then let’s tackle a volume conversion and density conversion.

Example 5: Unit Conversions

Mass

Problem: Convert 525 g to units of kg.

Solution: The mass is equal to 0.525 kg.

Volume

Problem: Convert 450 mL to units of m3.

Solution: The volume is 0.00045 m3. Note that here we needed to do a two-step conversion since we didn’t have a conversion factor directly from mL to m3.

Density

Problem: Convert 13.6 g/cm3 to units of g/mL.

Solution: The density is 13.6 g/mL since 1 g/cm3 = 1 g/mL. Using the conversion chart, we can start with any units on the chart (such as the bottom left corner) and end up at any other units.

Look back at the volume conversion chart. The one volume conversion factor that is commonly misunderstood is that 1,000,000 cm3 = 1 m3. You might be thinking, “I thought there were 100 cm in 1 m.” There are. But imagine a cube that is 1 m x 1 m x 1m. That is the same as 100 cm x 100 cm x 100 cm. Because we a multiplying 100 cm x 100 cm x 100 cm, we can fit 1,000,000 cm3 inside 1 m3!

Let’s put all this together and do a density problem that will require us to perform some unit conversions as well.

Example 6: Mass of a Gas

Problem: Two students argue about whether or not air has mass. One student says, “Since we know the density of air (see the table below), we can find the mass of the air in this room if we know its volume.” Show that this student is right by finding the mass of the air in a room that you estimate to be 6.0 m long, 4.0 m wide, and 2.5 m tall. (Assume the air is dry and it is at 25 °C and 1 atm.)

Solution: We’ll first find the volume of the room given its dimensions. A room that is 6.0 m by 4.0 m by 2.5 m will have a volume of 60 m3. We know the density of air (from the table above) is approximately 0.00123 g/mL. Next, let’s convert this density to units of kg/m3. We’ll do this so we can get the units of m3 to cancel in our mass calculation.

We find the mass of the air in the room to be 74 kg. This is no small mass. This is approximately the mass of an average-sized adult. While you might think that the mass of the air in the room you are in right now is very small, it is actually quite significant. We’ll see in our next lesson that this helps us understand why the air pressure at the surface of the earth is much larger than it is higher in the atmosphere. All the air in the atmosphere ‘weighs’ down on us because it has mass!

Check Your Understanding

Use the following questions to assess your understanding. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

1. You are asked to rank the densities of three different liquids (a, b, and c). You start by measuring the mass of an empty beaker. Next, you pour a sample of each liquid into the beaker and find the mass of the beaker and liquid together, as shown in the figure. How would you rank the densities of these fluids (from least dense to most dense)?

2. You find a container of an unknown clear liquid. You determine the mass of the liquid to be 240 g and its volume 260 mL. Using the table below, what might this liquid be?

3. Determine the correct equation used to solve for…

(A) Density

(B) Mass

(C) Volume

4. Using the conversion chart above, perform the following conversions:

Mass

(A) 255 g = ____________ kg

(B) ___________ g = 0.135kg

Volume

(C) 380 mL = ___________ L

(D) 380 mL = _________ cm3

(E) ___________ cm3 = 2 m3

Density

(F) 1.33 g/mL = _______ kg/L

(G) 1.33 g/mL = ______ kg/m3

5. A chamber with a volume of 36 m3 is filled with carbon monoxide gas. (Assume pressure of 1 atm and temperature of 25 oC). What is the mass of this gas in kilograms?