Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Lesson 1: Nuclear Radiation

Part b: Balancing Nuclear Equations

Part a:

Radioactive Decay

Part b: Balancing Nuclear Equations

Part c:

Nuclear Stability and Instability

The Big Idea

A nucleus changes its identity through a nuclear reaction. Those changes follow strict conservation rules. By ensuring mass number and atomic number remain balanced on both sides of the equation, we can track what particle is emitted and what new nucleus form.

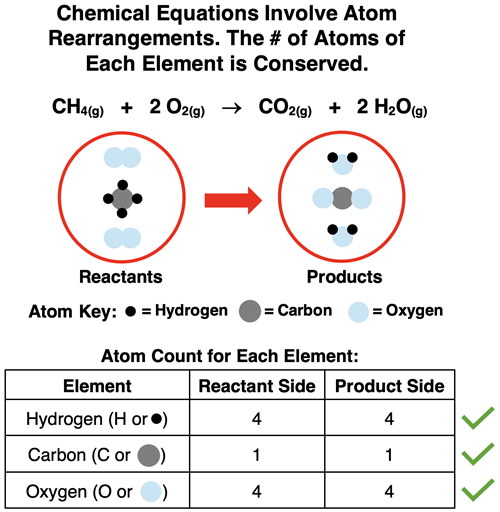

Chemical Reactions Revisited

Chemical reactions, as introduced in Chapter 8 of this Chemistry Tutorial, are quite different than the nuclear transmutations discussed in this chapter. Chemical reactions involve the breaking of bonds in the reactants, the rearrangement of atoms, and the formation of new bonds in the products. Chemical equations describe the result of these atom rearrangements. Because atoms are not created nor destroyed but simply rearranged, we observe the same number of atoms of each element on the reactant side as on the product side. The task of balancing a chemical equation involved the addition of coefficients in front of the formulae in an effort to balance atoms. Atom counts were performed for each element to ensure that the number of atoms on the reactant side equals the number of atoms on the product side of the equation.

Nuclear Transmutation

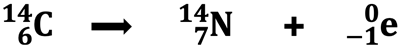

In Lesson 1a, we learned that certain isotopes of elements have unstable nuclei. These radioisotopes naturally undergo a transmutation, often into the nucleus of a different element. That is, we might start with the nucleus of a carbon-14 atom and end with the nucleus of a nitrogen-14 atom. Clearly, the atom of carbon is not conserved. This transmutation is represented by a nuclear equation like the one below for beta decay.

The isotope symbols in the equation consist of an element symbol, the corresponding atomic number, and the mass number of the isotope. One pattern that we ALWAYS observe is that the sum of the mass numbers (A) of all species on the reactant side equals the sum of the mass numbers for all species on the product side. We also ALWAYS observe that the sum of the atomic numbers (Z) are the same on the reactant side as on the product side. Just as we performed an atom count to ensure that a chemical equation is balanced, we could perform a mass number and atomic number count to ensure that a nuclear equation is balanced. This is shown below:

The isotope symbols in the equation consist of an element symbol, the corresponding atomic number, and the mass number of the isotope. One pattern that we ALWAYS observe is that the sum of the mass numbers (A) of all species on the reactant side equals the sum of the mass numbers for all species on the product side. We also ALWAYS observe that the sum of the atomic numbers (Z) are the same on the reactant side as on the product side. Just as we performed an atom count to ensure that a chemical equation is balanced, we could perform a mass number and atomic number count to ensure that a nuclear equation is balanced. This is shown below:

Law of Conservation of Mass and Charge

Law of Conservation of Mass and Charge

There are two fundamental principles that underly both a chemical equation and a nuclear equation. As we mentioned above, the principle is not the conservation of atoms as it does not apply to a nuclear equation. The two fundamental principles are the law of conservation of mass and the law of conservation of charge. Mass and charge are conserved in both chemical and nuclear equations.

Let’s look at nuclear equations through the lens of these two fundamental principles. Nuclear equations describe the changes in the nucleus. Protons and the neutrons give the nucleus its mass. The sum the protons and the neutrons is the mass number. We have observed that this sum is the same on the reactant and the product side, demonstrating the law of conservation of mass. Protons give the nucleus its charge (neutron have no overall charge). The atomic number describes the number of protons. Thus, the atomic number reflects the nuclear charge. We have observed that this sum of the atomic numbers is the same on the reactant and the product side, demonstrating the law of conservation of charge.

Let’s look at nuclear equations through the lens of these two fundamental principles. Nuclear equations describe the changes in the nucleus. Protons and the neutrons give the nucleus its mass. The sum the protons and the neutrons is the mass number. We have observed that this sum is the same on the reactant and the product side, demonstrating the law of conservation of mass. Protons give the nucleus its charge (neutron have no overall charge). The atomic number describes the number of protons. Thus, the atomic number reflects the nuclear charge. We have observed that this sum of the atomic numbers is the same on the reactant and the product side, demonstrating the law of conservation of charge.

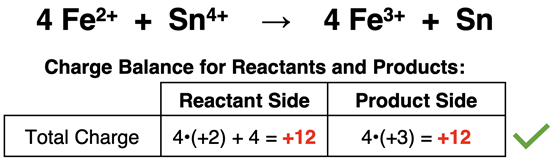

Now let’s look at chemical equations through the lens of these two fundamental principles. The mass of the species in a chemical equation is related to the number of atoms of each element )and their molar mass). That fact that the number of atoms of each element is the same on the reactant and the product side demonstrates the law of conservation of mass. In many instances, the reactants and products of a chemical equation have no overall charge. But if they are ions, we would observe a charge. The law of conservation of charge would state that the sum of the ion charges on the reactant side is equal to the sum of the ion charges on the product side. This is demonstrated by the net ionic equation for the oxidation-reduction reaction shown below.

Now let’s look at chemical equations through the lens of these two fundamental principles. The mass of the species in a chemical equation is related to the number of atoms of each element )and their molar mass). That fact that the number of atoms of each element is the same on the reactant and the product side demonstrates the law of conservation of mass. In many instances, the reactants and products of a chemical equation have no overall charge. But if they are ions, we would observe a charge. The law of conservation of charge would state that the sum of the ion charges on the reactant side is equal to the sum of the ion charges on the product side. This is demonstrated by the net ionic equation for the oxidation-reduction reaction shown below.

How to Write Balanced Nuclear Equations

The task of balancing a nuclear equation often involves determining the identity (and symbol) of an unknown particle or determining the identity (and symbol) of an unknown isotope. The process begins by writing down the symbols of ...

- All known isotopes on the reactant side (known as the parent nucleus)

- All known isotopes on the product side (known as the daughter nucleus)

- Any particles that are known to be present on either the reactant or product side

There is often an unknown particle or nucleus on the reactant or product side. Leave space for writing in its symbol once you have determined it. Conduct a mass balance and a charge balance to determine the A value (superscript) and the Z value (subscript) of any missing particle or nucleus. Once you known the A and Z values of the unknown, you can use

a periodic table (for isotopes) to determine the elemental symbol or your understanding of particles to determine the particle symbol (shown below).

The examples below demonstrate the use of this strategy. Additional practice is available in the

Check Your Understanding section and links to additional problems with feedback are listed in the

Before You Leave section.

Example 1 - Writing a Balanced Nuclear Equation

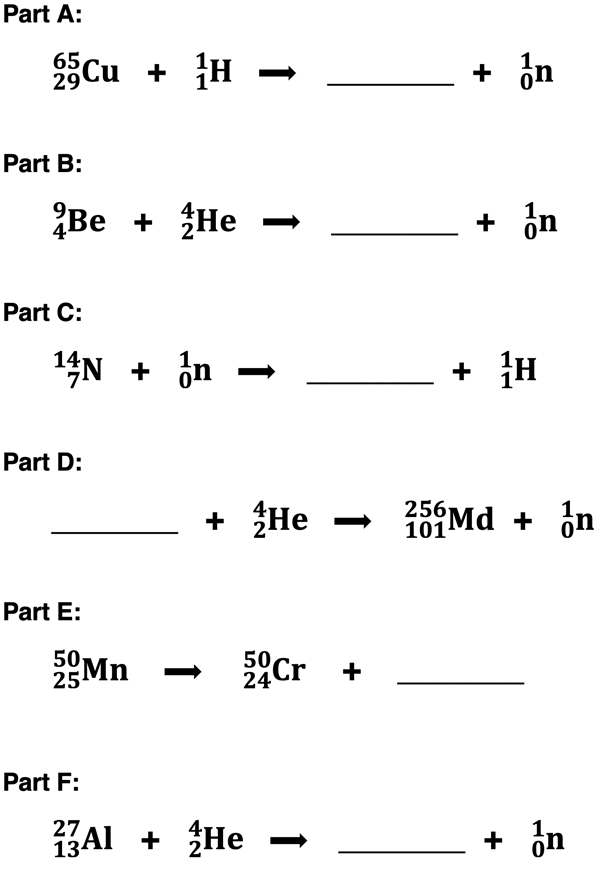

For the following nuclear equations, determine the symbol and the name of the unknown reactant or product. Tap a Check Answer button to view an answer and the solution.

Solution:

Example 2 - Writing a Balanced Nuclear Equation

Given the word equations, write the balanced nuclear equation and identify the name of the daughter nucleus. Tap a Check Answer button to view an answer and the solution.

a. A radium-222 nucleus undergoes alpha decay.

b. A boron-8 nucleus undergoes positron decay.

c. A silver-108 nucleus undergoes beta decay.

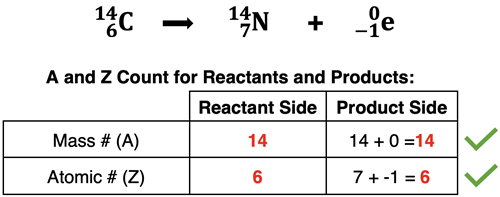

Example 3 - Writing a Balanced Nuclear Equation

The nuclear equation below describes a neutron bombardment reaction (to be discussed in Lesson 3). Identify the unknown product.

Before You Leave - Practice and Reinforcement

Practice definitely makes perfect ... and that’s what the rest of the page is about. It’s your turn to strengthen your understanding and put the ideas into practice. Here's some suggestions.

Check Your Understanding of Nuclear Equations

Use the following questions to develop your skill at writing balanced nuclear equations. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

1. Use appropriate isotope symbols and particle symbols to write balanced nuclear equations from the following word equations.

a. An americium-243 (Am-243) nucleus undergoes alpha decay.

b. A yttrium-85 (Y-85) nucleus undergoes positron emission.

c. A cobalt-57 (Co-57) nucleus undergoes electron capture.

d. A hydrogen-3 nucleus undergoes beta decay.

2. The following nuclear transmutations may be unfamiliar to you at the moment (but not by chapter’s end). An understanding of mass balance (A values) and charge balance (Z values) will allow you to determine the symbol of the missing particle or nucleus. Determine answers to Parts A through F; then tap the

Check Answers button to see how you did.