Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Lesson 2: Rates of Decay

Part a: Half-Life

Part a: Half-Life

Part b:

Radioactive Dating

The Big Idea

Radioactive decay happens at a predictable rate for large groups of atoms, and half-life is the measure that captures this behavior. It tells us how long it takes for half of a sample to decay, allowing us to model and calculate changes in radioactive materials over time.

Where are All the Radioisotopes?

Of the more than 3000 known isotopes, only about 250 do not undergo radioactive decay. More than 90% are radioactive! With this information, you might wonder why none of us are glowing in the dark, losing all our hair, or growing a third eye. With that many radioisotopes, it seems it should be a very radioactive world. It seems like we should all be characters on a video game called Fallout. Where are all these radioisotopes?

Of the more than 3000 known isotopes, only about 250 do not undergo radioactive decay. More than 90% are radioactive! With this information, you might wonder why none of us are glowing in the dark, losing all our hair, or growing a third eye. With that many radioisotopes, it seems it should be a very radioactive world. It seems like we should all be characters on a video game called Fallout. Where are all these radioisotopes?

Many radioisotopes decay quite rapidly and have undergone transmutation into a stable nuclei. Of the known radioisotopes, somewhere between 80 and 90 are seen in nature. This includes

- long-lived (decays slowly), primordial isotopes (about 35 radioisotopes); their existence is traced back to the formation of the solar system.

- short-lived daughters produced by the radioactive decay of the more abundant primordial isotopes like uranium and thorium; these are referred to as radiogenic.

- radioisotopes produced by the interaction of cosmic rays with elements on earth; these are referred to as cosmogenic. Carbon-14 and hydrogen-3 are examples.

The Periodic table below color-codes the elements according to their most stable isotope and its rate of decay. Of the first 82 elements (

1H to

82Pb), all but two (

43Tc and

61Pm) have one or more stable isotopes. All other elements (Z > 83) have no stable isotopes; all undergo radioactive decay. The

radioisotopes of these elements have varying decay rates. The color reflects the decay rate of the longest-lived isotope among them. The half-life value (t

1/2) provides a measure of the rate at which the isotope decays. We will discuss it thoroughly in the next section. And we will also take up the question of Where are All the Radioisotopes? again at

the end of the page. See

Naturally Occurring Radioisotopes.

What is Half-Life?

What is Half-Life?

The rate of decay of a radioisotope is expressed in terms of its half-life. The

half-life, denoted by the symbol

t1/2, is the time it takes for one-half of the atoms in a sample to decay. Suppose we start with 100.0 grams of a radioisotope. After a time equal to one half-life, there will be 50.0 g remaining. The sample, now 50.0 grams, will continue to decay until it is gone. So after a second half-life, it will have decayed in half a second time. There will be 25.0 g remaining. After a third half-life, the amount of 25.0 g will be reduced in half again; there will be 12.5 g remaining. This pattern will continue until the radioisotope is completely changed into its

daughter isotope. This pattern of change is illustrated in the tables below.

Radioisotopes have widely varying half-life values. Some decay quite rapidly, with half-lives in microseconds. Other unstable isotopes have half-lives measured in the millions, billions, and trillions of years. Half-life is a main factor in determining the prevalence of a radioisotope in our environment. All else being equal, radioisotopes with very long half-lives are far more likely to still be present in our environment today. An isotope with a very short half-life (minutes or less) will not be observed. They are highly

active (i.e., radioactive) and have decayed into other nuclides. Most isotopes of the transuranium elements (Z > 92) are produced in nuclear facilities by bombardment reactions and have very short half-lives; these radioisotopes account for hundreds of the known radioisotopes. Isotopes like potassium-40, thorium-232, and uranium-238 have very long half-lives. These are present in the Earth’s crust in measurable amounts. Fortunately, their long half-lives mean they are less

active (i.e., less radioactive), emitting radiation at low rates.

How to Determine the Amount of a Radioisotope that Remains?

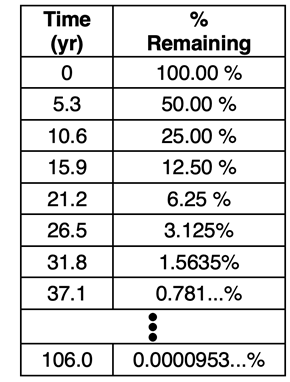

The half-life concept can be used to predict the amount of a radioisotope that will be present after a certain amount of time. Let’s consider cobalt-60, a radioisotope that has historically been used to treat cancer. It’s half-life is 5.3 years. Let’s suppose a certain quantity is purchased by a cancer treatment center, stored in a closet, and forgotten - an unlikely event, but useful for our illustration. Since we know the t

1/2 value, we can predict the percentage of the original quantity that remains after every 5.3 years. This is illustrated in the table at the right. The percentage, like the amount in grams, is reduced in half after each additional half-life. After 20 half-lives - 106.0 years - the percentage that remains is miniscule; it is less than 1/10,000

th of a percent.

These tables are commonly used in a Chemistry course to solve problems similar to those in Examples 1 through 3. The problems usually fall into one of two types:

- Determine the percent remaining after a specified time

- Determine the time that elapses before a specified amount of the original material remains.

Both problem types can be answered using a table like the one above. The first column is the time - either in a unit such as years or expressed in terms of half-lives. From row-to-row, the value increases by one half-life (usually a time stated in the problem). The second column refers to the amount remaining. It could be the percent that remains, the fraction that remains, or a mass in grams (or comparable unit). From row-to-row, the value is changed to an amount that is one-half the previous row.

Example 1 - Determining the Percentage Remaining After a Specified Time

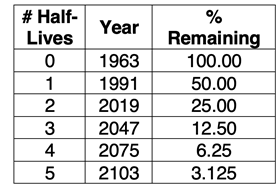

Strontium-90 is one of the many radioactive wastes of nuclear weapons. This isotope is especially dangerous if it enters the food supply. Strontium behaves like calcium, becoming incorporated into the bone structure. The main source of strontium-90 in the environment is the fallout from above-ground nuclear weapons testing carried out in the 1950s and 1960s. These tests were banned in 1963. Yet, some strontium-90 still remains in the environment. Strontium-90 has a half-life of 28 years. Use a decay table to estimate the percentage of the 1963 amount that ...

- still remained in the environment in 1991.

- still remained in the environment in 2019.

- will still be remaining in the environment in 2050.

- will still be remaining in the environment in 2100.

Solution

We can produce a table with three columns as shown. The year column is increased from row-to-row by 28 years. The percent remaining is one-half of the previous row.

We can use the table to answer the four questions. We can only estimate the answers to parts c and d since 2050 and 2103 are not a whole number of half-lives after the starting year. (We introduce an equation later that can be used for more precise answers.)

- 50.00% remains in 1991.

- 25.00% remains in 2019.

- Approximately 6% remains in 2050 (a little less than 6.25%).

- Approximately 3% remains in 2100 (a little less than 3.125%)

Example 2 - Determining the Amount Remaining After a Specified Time

A nuclear physicist recently purchased an 800.00-mg sample of a radionuclide that has a half-life of 4.0 days. If the sample were never used, what mass will be present ...

- after 12 days?

- after 20 days?

- after 25 days

Solution

Solution

We can produce a table with two columns as shown. We have used mass as the amount; it is reduced in half from row-to-row. The table is used to answer the parts a and b directly since the given time is a whole number of half-lives. We can only estimate the answer to part c since 25 days is not a whole number of half-lives. Since the relationship between time and mass is not linear, we cannot simply extrapolate between the 24-day and 28-day mass values. (We introduce an equation later that can be used for more precise answers.)

- 100.00 mg remain after 12 days.

- 25.00 mg remain after 20 days.

- Less than 12 mg remain after 25 days (somewhere between 12 mg and 6.25 mg).

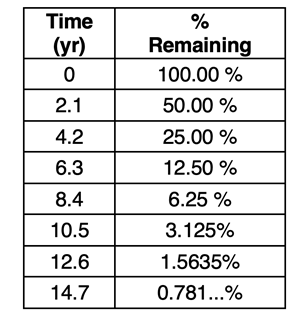

Example 3 - Determining the Time Elapsed Before a Specified Amount Remains

A radioisotope has a half-life of 2.10 years. Estimate the time elapsed before

- 20.0% of it remains.

- 10.0% of it remains.

- 1.0% of it remains.

Solution

We can produce a table with two columns as shown. The percentage is the amount that is reduced in half from row-to-row. We can use the table to answer the three questions. We will have to estimate all answers since the specified percentages do not appear in the table. (We introduce an equation later that can be used for more precise answers.)

- It will take approximately 5 years before 20% remains (more than 4.2 years and less than 6.3 years).

- It will take approximately 7 years before 10% remains (more than 6.3 years and less than 8.4 years).

- It will take approximately 13 years before 1% remains (more than 12.6 years and less than 14.7 years).

Radioactive Decay Curves

A few of our data sets above have shown the percent remaining as a function of the number of half-lives. If a plot of percent remaining vs. # of half-lives would look like the plot below. The curve is consistent with a quantity undergoing

exponential decay. While the amount that decays during any individual half-life varies, itis always one-half of the amount present at the beginning of the time period. While the rate of decay decreases over time, that rate at any given instant is always one-half of whatever amount is present at that instant.

How to Determine the Half-Life

All radioactive decay curves always have this same

exponential shape. As we will see, they can be used as a tool to determine the half-life of a radioisotope. Using the half-life definition, points can be read off the graph to determine how much time it takes for the amount to be

halved. Best practices involve performing several

trials and averaging the results. This is illustrated in Example 4.

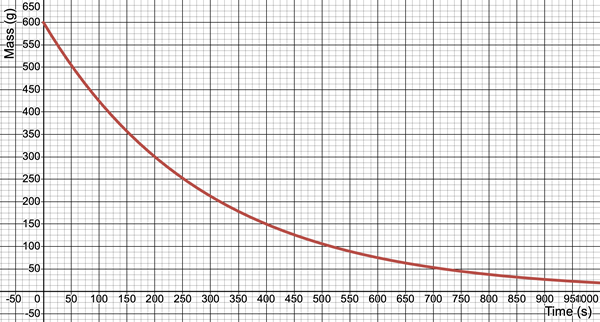

Example 4 - Determination of Half-Life from a Decay Curve

Consider the plot of the mass of a radioactive material as a function of time. Use the graph to determine the half-life of the material.

Solution:

Three “trials” are performed. Each trial involves reading values from the graph to determine the time elapsed between two points that have mass values with ratios of 1:2. The selected points are shown on the graph below. The work is shown below the graph:

Trial 1 (in blue): The mass decreased from 240.0 g to 120.0 g between the times of 0.0 s and 150.0 s. This is consistent with a t

1/2 value of 150.0 s.

Trial 2 (in green): The mass decreased from150.0 g to 75.0 g between the times of 100.0 s and 250.0 s. This is consistent with a t

1/2 value of 150.0 s (the time elapsed between 100.0 s and 250.0 s).

Trial 3 (in purple): The mass decreased from 60.0 g to 30.0 g between the times of 300.0 s and 450.0 s. This is consistent with a t

1/2 value of 150.0 s (the time elapsed between 300.0 s and 450.0 s).

Since all three trials resulted in the same t

1/2 value, there is no need to average. We can conclude that ...

t1/2 = 150.0 s

“Advanced” Half-Life Mathematics

An understanding of half-life leads to the following verbal statements:

- After one half-life, 50.00% of the original amount remains

- After two half-lives, 25.00% of the original amount remains

- After three half-lives, 12.50% of the original amount remains

- After four half-lives, 6.25% of the original amount remains

- After five half-lives, 3.125% of the original amount remains

There is a clear

divide-by-2 pattern in these statements. For each half-life that elapses, the new amount is the previous amount divided by 2. You might say that:

The amount of the substance (N) at some time (t) is equal to the original amount (No) divided by 2n where n is the number of half-lives that have elapsed. The number of half-lives is simply t/t1/2.

If you understand this divide-by-2 pattern, then you could write an equation that expresses

N as a function of time (

t).

N = No / 2n where n = # of half-lives = t/t1/2

This equation can be used to calculate the amount of a radioisotope (

N) at time

t as long as the original amount (

No) and the half-life (

t1/2) are known. Unlike the table method used in Examples 1-3, this equation can be used to determine with precision the amount that remains even if the time is not a whole number multiple of the half-life. We demonstrate its use in

Example 5 and

Example 6.

The above equation can be algebraically manipulated to derive an equation for calculating the time (

t) for the original amount (

No) to be reduced to some specified amount (

N). The equation is

t = - t1/2 • ln(N/No) / ln(2)

where

ln represents the natural logarithm function. The ratio

N/No is referred to as the fraction remaining and can be represented by the variable

f. The equation can be rewritten as

t = - t1/2 • ln(f) / ln(2)

This equation can be used to determine the time it takes for a specified fraction of the original amount to remain. The fraction remaining can be determined as the

N/No ratio (if given) or by dividing the percent remaining (if given) by 100. The use of this equation is demonstrated in

Example 7.

Example 5 - Determining the Remaining Amount of a Radioisotope

A nuclear physicist recently purchased an 800.00-mg sample of a radionuclide that has a half-life of 4.0 days. If the sample were never used, what mass will be present ...

- after 12.0 days?

- after 17.8 days?

- after 25.0 days?

Solution:

The solution for all three parts will involve determining n from the time and the given half-life (4.0 days) and then using it in the equation as the exponent on 2.

a. n = t / t

1/2= 12.0 days / 4.0 days = 3.0

N = N

o / 2

n = 800.0 mg / 2

3 =

100.00 mg

b. n = t / t

1/2= 17.8 days / 4.0 days = 4.45

N = N

o / 2

n = 800.0 mg / 2

4.45 =

36.60 mg

c. n = t / t

1/2= 25.0 days / 4.0 days = 6.25

N = N

o / 2

n = 800.0 mg / 2

6.25 =

10.51 mg

Example 6 - Determining the Remaining Amount of a Radioisotope

Thorium-234 has a half-life of 24.1 days. A lab technician purchases a 215-gram sample for an upcoming study. The technician becomes unexpectedly delayed and the technician does not get to the thorium until 67.3 days later. What mass of the original radioisotope still remains?

Solution:

We know the values of No (215 g), t

1/2 (24.1 d), and t (67.3 d). The equation can be used to determine the number of half-lives (n) and the mass remaining (N).

n = t / t

1/2= 68.3 days / 24.1 days = 2.83402 ....

N = N

o / 2

n = 215 g / 2

2.83402 .... =

30.2 g (rounded from 30.1517 ... g)

Example 7 - Determining the Time Required for a Specific Fraction to Remain

A radioisotope has a half-life of 2.10 years. Estimate the time elapsed before

- exactly 20.0% of it remains.

- exactly 10.0% of it remains.

- exactly 1.0% of it remains.

Solution:

This is identical to Example 3, which we answered using a table of data. In

Example 3, we provided estimated answers since each percent was not indicated in the table. We are smarter now and have an equation to determine precise answers in Example 7. We will begin by converting the percent remaining to the fraction remaining; this involves dividing by 100. Then we will use the equation

t = - t1/2 • ln(f) / ln(2) to calculate the time.

a. f = % Remaining / 100 = 20.0% / 100 = 0.200

t = - t

1/2 • ln(f) / ln(2) = - 2.10 yr • ln(0.200) / ln(2) =

4.88 yrs

b. f = % Remaining / 100 = 10.0% / 100 = 0.100

t = - t

1/2 • ln(f) / ln(2) = - 2.10 yr • ln(0.100) / ln(2) =

6.98 yrs

c. f = % Remaining / 100 = 1.0% / 100 = 0.010

t = - t

1/2 • ln(f) / ln(2) = - 2.10 yr • ln(0.010) / ln(2) =

13.95 yrs

Naturally Occurring Radioisotopes

With an understanding of half-life and rates of decay, we can return to the original question of

Where are All the Radioisotopes? The table below a representative listing of the most common isotopes among the 80-90 naturally occurring radioisotopes, It is more of an illustration than an exhaustive list. The isotopes are grouped according to their origin - primordial, radiogenic, or cosmogenic. The atomic number (Z) and half-life (t

1/2) is also stated.

Five of the radioisotopes in the table are long-lived primordial isotopes. Their half-lives are longer than the age of the Earth. These radioisotopes likely originated from the supernovae explosions of older stars. They were captured during the formation of our Solar System and still exist today because of their slow decay rates.

Four of the radioisotopes are radiogenic. They are produced by the decay of two of most common primordial isotopes - thorium-232 and uranium-238. Because they are continually produced, we can observe them in nature in measurable amounts. These are not the only

daughter nuclei in the decay chains of these parent isotopes. Many of the

daughter nuclei have short half-lives; they are typically not observed since they decay shortly after production.

Three of the listed isotopes are cosmogenic. They are produced as cosmic rays from space bombard nitrogen and oxygen atoms in the upper atmosphere, initiating a chain of nuclear reactions that end with these isotopes. While their half-life is not extremely long compared to the other isotopes, there is a continued source of production - the bombardment of Earth by cosmic rays from space. These radioisotopes find their way to the lower atmosphere and Earth. For instance, hydrogen-3 is quickly incorporated into water molecules and enters Earth’s water cycle. It is present in very trace amounts in rivers, oceans, and groundwater.

Before You Leave - Practice and Reinforcement

Now that you've done the reading, take some time to strengthen your understanding and to put the ideas into practice. Here's some suggestions.

Check Your Understanding of Half-Life

Use the following questions to assess your understanding. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

1. Which elements or groups of elements do not have any stable isotopes?

2. The half-life of a radioisotope provides a measure of _______.

- how old the radioisotope is

- the type of decay that it undergoes

- the rate at which it undergoes decay

- how much of the radioisotope is present

3. Which would you rather be carrying around in your pocket and why - a sample of a radioisotope with a short half-life or a sample of a radioisotope with a long half-life?

- Seriously dude? Neither.

- Whichever one survives the washing machine cycle better. I always forget to empty my pockets.

- Short half-life. They are worth more money because there are less of them. And they're really hot!

- Long half-life. They decay very slowly and release radiation at a low rate. This results in less exposure.

4. If the half-life of a radioisotope is a small number, then it _____

- decays rapidly

- decays slowly

- does not decay at all

5. Use the decay curve below for a radioactive sample to determine its half-life.

6. Fill in the blanks in the following paragraph:

A radioisotope with a half-life of 2.0 minutes is measured to have a mass of 8.00 grams. After 2.0 minutes, its mass will be _______ grams. After 6.0 minutes, its mass will be _______ grams. And after 10.0 minutes, its mass will be _______ grams.

7. A radioisotope has a half-life of 22.0 minutes.

a. How much time would elapse before a sample contains 50% of its original amount?

b. How much time would elapse before a sample contains 12.5% of its original amount?

8. Thorium-234 has a half-life of 24.1 days. A lab technician purchases a 48.60-gram sample for an upcoming study. The technician becomes unexpectedly delayed and the technician does not get to the thorium until 58.1 days later. What mass of the original radioisotope still remains?

9. Consider a radioisotope having a half-life of 4.50 days. The initial mass of the radioisotope was measured to be 480.00 grams. Determine the time elapsed (in days) before the mass becomes …

a. ... 240.00 grams

b. ... 120.00 grams

c. ... 72.50 grams

d. ... 43.60 grams