Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Lesson 1: Nuclear Radiation

Part a: Radioactive Decay

Part a: Radioactive Decay

Part b:

Balancing Nuclear Equations

Part c:

Nuclear Stability and Instability

The Big Idea

Radioactive decay reveals a fundamental truth about matter: some atomic nuclei are inherently unstable, and over time they spontaneously emit particles or radiation to reach stability. This page describes the various decay pathways by which an unstable nuclei achieves stability.

What is Nuclear Chemistry?

The adjective nuclear has a habit of generating fear and alarm among a wide cross-section of the population. Nuclear war, nuclear bombs, nuclear waste, nuclear accident, and even nuclear power will incite images (often appropriately) of a wasteland of dead vegetation and bodies. With little understanding of what nuclear chemistry involves, a person’s instant reaction to the use of the adjective nuclear is negative and pessimistic. Yet the reality is that nuclear energy and nuclear medicine offer our generation so much benefit, provided we both understand and revere its abilities.

The adjective nuclear has a habit of generating fear and alarm among a wide cross-section of the population. Nuclear war, nuclear bombs, nuclear waste, nuclear accident, and even nuclear power will incite images (often appropriately) of a wasteland of dead vegetation and bodies. With little understanding of what nuclear chemistry involves, a person’s instant reaction to the use of the adjective nuclear is negative and pessimistic. Yet the reality is that nuclear energy and nuclear medicine offer our generation so much benefit, provided we both understand and revere its abilities.

We have discussed a lot of chemistry in the first 18 chapters of this Chemistry Tutorial. Much of that chemistry has pertained to the electrons that surround the nucleus of atoms. Atoms share and transfer those electrons in an effort to attain a stable octet of outer shell electrons. Chemical reactions occur in an effort to stabilize the electron shells of atoms. The importance of the nucleus has seldom been emphasized. It’s role has been mostly restricted to attracting the electrons that are in shells surrounding the nucleus.

There’s more to the story of stability than a discussion of the electron shells. In this chapter, we will learn the rest of the story - the story of the nucleus. The nucleus is the location of protons and neutrons. The protons and neutrons are also important to the stability of the atom. Depending on the relative numbers of each, a nucleus can be stable or unstable. And if unstable, it will undergo a change or transmutation to become stable. Nuclear chemistry is a study of this transmutation of the nucleus. We wish to understand why, how, and how often a nucleus changes and the effect that those changes have on the nucleus and its surroundings. We will begin the study with a review of isotopes.

Isotopes and Radioisotopes

Isotopes and Radioisotopes

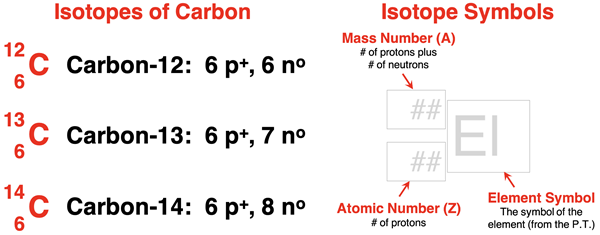

As we learned in Chapter 3 of this Chemistry Tutorial, atoms of an element exist as a variety of different isotopes. Every atom of the same element always has the same number of protons, known as the atomic number. But atoms of the same element can have varying number of neutrons. Isotopes are two or more forms of the same element that differ in terms of the number of neutrons. This difference means that isotopes will have different mass numbers.

As an example, there are three naturally-occurring isotopes of carbon. They are carbon-12, carbon-13, and carbon 14. Each has six protons. The numbers 12, 13, and 14 refer to the mass number of the isotope. Mass numbers indicate the number of protons (p+) plus neutrons (no). These three isotopes of carbon contain 6, 7, and 8 neutrons respectively.

A type of symbol, creatively referred to as an isotope symbol, is used to represent the isotope of an element. The symbol lists the elemental symbol of the element, preceeded by a superscript and a subscript. The superscript is the mass number (A). The subscript is the atomic number (Z). Protons and neutrons give a nucleus its mass. This is why we refer to the total number of these nucleons as the mass number. The protons give the nucleus its charge. Mass and charge are the two fundamental attributes of a nucleus. The isotope symbols for the three naturally-occurring isotopes of carbon are shown below.

The nuclear stability of an isotope depends upon the size of the nucleus and the ratio of neutrons to protons within the nucleus. (This will be addressed thoroughly in Lesson 1c.) Not all isotopes have stable nuclei. Those isotopes with unstable nuclei are referred to as radioisotopes. For carbon, carbon-12 and carbon-13 nuclei have stable nuclei. Carbon-14 is a radioisotope. Because it is unstable, carbon-14 atoms undergo a transmutation process known as radioactive decay or nuclear decay.

The nuclear stability of an isotope depends upon the size of the nucleus and the ratio of neutrons to protons within the nucleus. (This will be addressed thoroughly in Lesson 1c.) Not all isotopes have stable nuclei. Those isotopes with unstable nuclei are referred to as radioisotopes. For carbon, carbon-12 and carbon-13 nuclei have stable nuclei. Carbon-14 is a radioisotope. Because it is unstable, carbon-14 atoms undergo a transmutation process known as radioactive decay or nuclear decay.

Radioactive Decay

The concept of decay likely seems unpleasant. Radioactive decay doubles the unpleasantry. We can think of radioactive or nuclear decay as the process of changing the composition or parts of the nucleus. When the process is over, we have a different nucleus with a different composition. The process of radioactive decay involves a nucleus undergoing transmutation (i.e., change) while emitting radiation. Examples of radiation that you are already familiar with are ...

The concept of decay likely seems unpleasant. Radioactive decay doubles the unpleasantry. We can think of radioactive or nuclear decay as the process of changing the composition or parts of the nucleus. When the process is over, we have a different nucleus with a different composition. The process of radioactive decay involves a nucleus undergoing transmutation (i.e., change) while emitting radiation. Examples of radiation that you are already familiar with are ...

- visible light waves from a lamp.

- radio waves from the antenna of a radio station transmitting tower

- microwaves emitted by the magnetron of a microwave oven

- infrared waves sent from a hand-held remote to a television set

- ultraviolet waves from the sun that cause sunburns as a result of over-exposure

- the x-rays used to detect broken bones

Each of these waves are part of the

electromagnetic spectrum introduced in

Chapter 5. Electromagnetic (EM) waves exist with a range or spectrum of wavelengths (

l) and frequencies (f). The spectrum is divided into regions. The lower frequency regions - radio, microwave, infrared, and visible - are harmless; we refer to these regions as

non-ionizing radiation. The higher frequency regions - ultraviolet, x-ray, and gamma rays - have sufficient energy to knock electrons off atoms and break chemical bonds. These forms are referred to as

ionizing radiation.

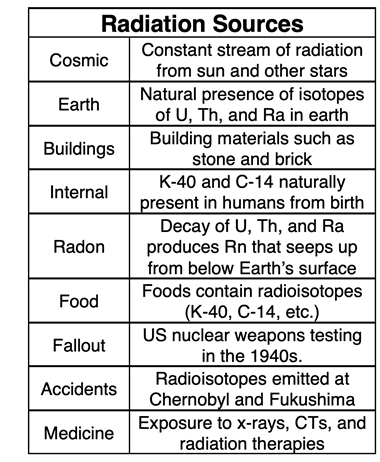

Unstable nuclei undergoing radioactive decay is more commonplace than you would think. Of the 118 known elements, there are approximately 3000 isotopes. There are 251 stable isotopes (though some sources will add a couple dozen more). The rest are

radioisotopes. Unstable radioisotopes of uranium, radium, thorium, and potassium in the Earth’s crust release radiation. Radon gas that seeps up from the ground consists of radioisotopes that undergo decay. Many radioisotopes are naturally present in the food we eat. Building materials, cosmic rays from outer space, drinking water, and television sets expose us to radiation.

Radiation is not a substance that leaks out of a nucleus. It is energy in the form of waves or particles that is released as an unstable nucleus rearranges itself to change into a stable nucleus. Radioactive decay is not explosive or sudden. Radioactive decay is nature’s way of reassembling the unstable into the stable. When it occurs, nature is doing some house-cleaning.

Radioactive decay is natural and spontaneous. At the macroscopic level, it is highly predictable, allowing one to predict how much of a radioisotope will decay in a second, a minute, a day, a year, and a century. Unlike chemical processes, it occurs at a rate that is independent of temperature and pressure. It cannot be controlled. It cannot be modified. It cannot be turned or off. Radioactive decay just happens. Nature is tidying up. Nature is becoming more stable.

The radiation released during a nuclear decay process comes in two forms:

- high-energy electromagnetic waves known as gamma rays

- tiny particles such as alpha particles and beta particles

Let’s explore these forms of radiation in detail.

Alpha Decay

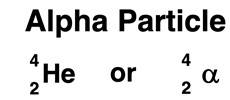

Alpha decay is a type of radioactive decay in which the nucleus releases an alpha particle in an effort to achieve stability. An

alpha particle is a helium-4 nucleus. It is a particle consisting of two protons and two neutrons. It has an atomic number (or charge) of +2 and a mass number of 4. An alpha particle is represented by the symbol shown at the right. The decay of radon-222 occurs as an alpha decay process. It is represented by the following

nuclear equation.

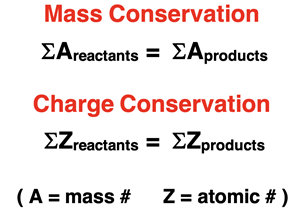

Alpha decay causes the unstable nucleus to decrease its mass number (A) by 4 and its atomic number (Z) by 2. An inspection of the equation shows both mass and charge conservation. That is, the sum of the mass numbers on the reactant side equals the sum of the mass numbers on the product side. Similarly, the sum of the atomic numbers on the reactant side equals the sum of the atomic numbers on the product side.

Of all decay particles, the alpha particle has the greatest mass, giving it the capability to do significant damage to biological tissue of the human body. However, it has a very low

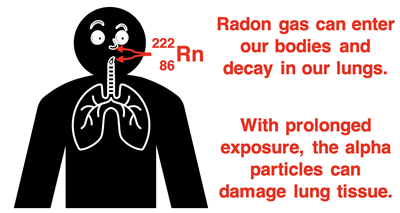

penetrating ability. That is, it can be stopped by a sheet of paper, by clothing, and by the skin. Radon gas is of great environmental concern because it bypasses our skin as it is breathed into the lungs. When the decay of radon occurs inside the lungs, the alpha particle can damage lung tissue. Radon gas is the second leading cause of lung cancer (as of this writing). In certain areas of the country, it seeps into our homes through cracks in the foundation. Improving ventilation, sealing foundation cracks, and using a radon-mitigation system can significantly reduce the risk of harm from radon gas.

Beta Decay

Beta Decay

Beta decay is a second type of radioactive decay process. Beta decay results in the release of a beta particle. A

beta particle is a high-speed electron with a relatively negligible mass and a charge of -1. A beta particle is represented by the symbol shown at the right. The decay of carbon-14 occurs as a beta decay process. It is represented by the following

nuclear equation.

During beta decay, a neutron converts to a proton, resulting in the ejection of an electron from the nucleus. Beta decay causes the unstable nucleus to increase its atomic number (Z) by 1 with no change in its mass number (A). Just like the alpha decay of radon-222, mass and charge is conserved during the beta decay of carbon-14. This is a basic principle we will observe throughout the chapter.

A beta particle has considerably less mass than an alpha particle. This gives beta particle less capability of ionizing human tissue. But it also gives it a greater penetrating ability. Beta particles can penetrate clothing and the outer layers of skin. A few millimeters of plastic or a thin sheet of aluminum can provide shielding from beta particles.

Gamma Decay

Gamma decay is a third type of radioactive decay process that results in the release of a gamma ray. A

gamma ray is a high energy electromagnetic wave having no mass and no charge. The symbol for a gamma ray is shown at the right. Gamma decay most often occurs when a nucleus in an excited state (referred to as a

metastable nucleus) releases energy in the form of a gamma ray as it transitions towards a more stable ground state. Gamma decay does not change the identity of the nucleus; it simply changes its energy. The gamma decay of nickel-60 in an excited state to the ground state is represented by the following

nuclear equation. (The asterisk indicates a nucleus in an excited state.)

Gamma radiation is an ionizing form of electromagnetic radiation. With no mass and no charge, it has less ability to ionize tissue and organs than alpha and beta particles. However, what makes it most harmful is its penetration ability. Gamma rays can penetrate deep into the body, causing damage to tissues and organs. An inch or more of lead and several feet of concrete are often used as shields for gamma rays. The required thickness of lead or concrete depends upon the intensity of the gamma source and the distance from the source.

Positron Decay

Our earliest understanding of radioactivity was focused on alpha, beta, and gamma rays because these were emissions that were directly detectable and measurable. Today we recognize two additional pathways by which unstable nuclei reach stability - positron decay and electron capture. Positron decay involves the release of a positron. A

positron is a positively charged particle with a mass identical to the electron’s. It is sometimes referred to as the counterpart or anti-particle of the electron. A positron is represented by the symbol shown at the right. Magnesium-23 will achieve stability through positron decay into sodium-23. It is represented by the following

nuclear equation.

During positron decay, a proton converts to a neutron, resulting in the ejection of a positron from the nucleus. Positron decay causes the unstable nucleus to decrease its atomic number (Z) by 1 with no change in its mass number (A). Once again, mass and charge are conserved in the process.

Electron Capture

Electron capture is a fifth process by which an unstable nucleus can attain stability. Unlike the previous four processes, there is no emitted particle displayed in the nuclear equation. During electron capture, an electron in a lower energy shell is pulled into the nucleus by a proton. Once captured, the proton and electron transform into a neutron. Potassium-40 sometimes achieves stability by electron capture, as represented by the following

nuclear equation:

Electron capture causes the unstable nucleus to decrease its atomic number (Z) by 1 with no change in its mass number (A).

Summary of Radioactive Decay Processes

Radiation involves the release or emission of a high-energy electromagnetic wave or a tiny particle. We have seen four types of emissions in the decay processes described above. The table summarizes the four types.

Finally, the five decay processes are summarized in the following table.

Before You Leave - Practice and Reinforcement

Now that you've done the reading, take some time to strengthen your understanding and to put the ideas into practice. Here's some suggestions.

- Try our Concept Builder titled Nuclear Decay. Any one of the three activities provides a great follow-up to this lesson.

- The Check Your Understanding section below includes questions with answers and explanations. It provides a great chance to self-assess your understanding.

- Download our Study Card on Radioactive Decay. Save it to a safe location and use it as a review tool.

Check Your Understanding of Radioactive Decay

Use the following questions to assess your understanding. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

1. Calling an atom radioactive involves making a comment about the _____ of the atom.

- parents

- nucleus

- valence electrons

- moral character

2. Which of the following pairs are isotopes? Select all that apply.

- potassium-39 and potassium-40

- uranium-238 and neptunium-238

- sodium-24 and chromium-50

3. The word

radioactive is a scary word to many people … but it really doesn't have to be. A radioactive atom is an atom that …

- glows in the dark when light shines on it, causing observers to remark - “That’s rad!”

- has mutated from its normal form and now poses a danger to society

- has soaked in radioactive poison from a radioactive source and is harmful as a result

- spontaneously decomposes to other nuclei, ejecting one or more particles during the process

4. Which of the following statements are true of nuclear equations? Select all that are TRUE.

- There are the same number of atoms of each element on left and right side of the equation.

- The amount of mass on the left side of the equation = the amount of mass on the right side.

- The amount of nuclear charge on the left side of the equation = the amount of nuclear charge on the right side.

5. This page discusses five types of radioactive decay processes. They are alpha particle decay (

A), beta particle decay (

B), gamma decay (

G), positron decay (

P), and electron capture (

EC). Match each of the following statements to one or more of the decay processes; list letters

A,

B,

G,

P, and

EC in the blanks. Choose all that apply for each statement.

- A high-speed electron is emitted from the decaying nucleus.

- The particle is located on the reactant side.

- A high-energy photon is produced during this decay process.

- A nucleus decays and there is a helium nucleus produced.

- Involves the transforming of a nucleus into the nucleus of a different element.

- The decay of thorium-230 to radium-226 is an example.

- The decay of mercury-201 to gold-201 is an example. (Choose two.)

6. Match each of the statements below to one or more decay process. Select the letters

A,

B,

G,

P, and

EC for alpha particle decay (

A), beta particle decay (

B), gamma decay (

G), positron decay (

P), and electron capture (

EC). For each statement, choose all that apply.

- Causes the decaying nucleus to change to a new nucleus with a smaller mass number.

- Causes the decaying nucleus to change to a new nucleus with a smaller atomic number.

- Causes the decaying nucleus to change to a new nucleus with a greater atomic number.

- Leads to no overall change in the mass number.

- Has the net effect of decreasing the atomic number by 2.

- Has the net effect of decreasing the atomic number by 1.