Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Lesson 1: Nuclear Radiation

Part c: Nuclear Stability and Instability

Part a:

Radioactive Decay

Part b:

Balancing Nuclear Equations

Part c: Nuclear Stability and Instability

The Big Idea

Whether a nucleus is stable or unstable depends on the delicate balance of forces acting inside it. The interplay between the strong nuclear force and electrostatic repulsion, along with the neutron-to-proton ratio, determines whether a nucleus remains intact or undergoes radioactive decay.

About the Nucleus

The nucleus of atoms is composed of protons and neutrons. The protons are positively charged. The neutrons are electrically neutral. These nucleons (a term used to describe protons and neutrons) pack together closely as depicted at the right. They are not believed to be as rigid and spherical as shown. Protons exert attractive, electrostatic forces upon the negatively charged electrons in the shells surrounding the nucleus. And as we will see, the neutrons serve the function of holding the nucleus together.

The nucleus of atoms is composed of protons and neutrons. The protons are positively charged. The neutrons are electrically neutral. These nucleons (a term used to describe protons and neutrons) pack together closely as depicted at the right. They are not believed to be as rigid and spherical as shown. Protons exert attractive, electrostatic forces upon the negatively charged electrons in the shells surrounding the nucleus. And as we will see, the neutrons serve the function of holding the nucleus together.

The diameter of a typical nucleus is about 1/100,000th the diameter of the atom. If the atom were the size of a football stadium, then the nucleus would be the size of a pea located at its center. Yet, it possesses more than 99.99% of the atom’s mass. This large mass in a very small space makes the nucleus incredibly dense. In fact, the density of nuclear matter is estimated to be ~2x1014 g/mL and independent of the actual element. This makes the nucleus 10-trillion times more dense than liquid mercury.

The Nuclide Chart

Atoms of the same element always have the same number of protons but can have a varying number of neutrons. This gives rise to the existence of isotopes - forms of the same element that have a different number of neutrons. There are more than 3000 known isotopes of the 118 elements. Less than 10% of these isotopes are stable isotopes that will never undergo radioactive decay. The other 90% or more are radioactive. They undergo some form of radioactive decay, releasing a decay particle and energy in an effort to become stable.

Atoms of the same element always have the same number of protons but can have a varying number of neutrons. This gives rise to the existence of isotopes - forms of the same element that have a different number of neutrons. There are more than 3000 known isotopes of the 118 elements. Less than 10% of these isotopes are stable isotopes that will never undergo radioactive decay. The other 90% or more are radioactive. They undergo some form of radioactive decay, releasing a decay particle and energy in an effort to become stable.

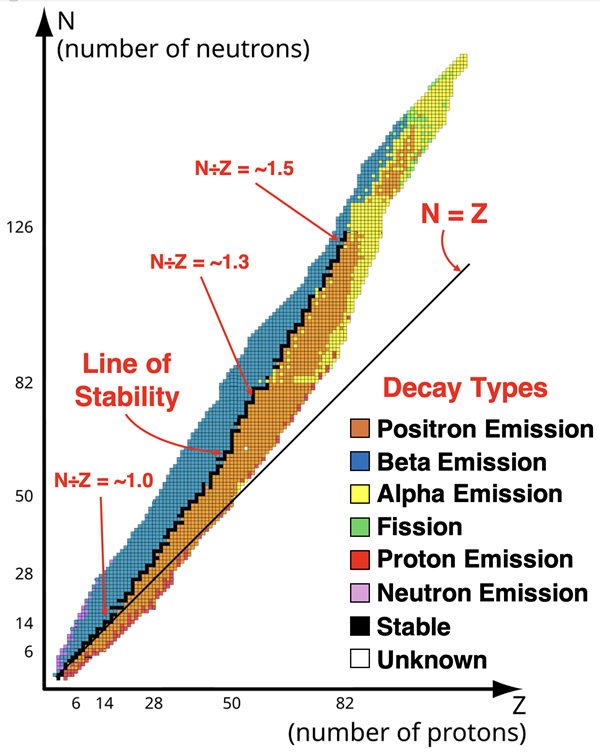

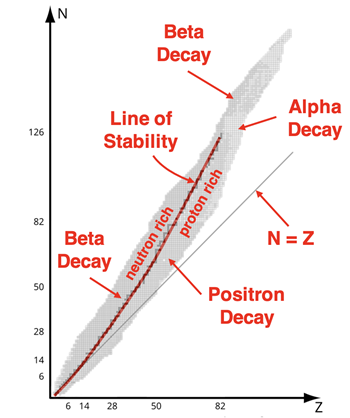

A plot of the number of neutrons (N) vs. the number of protons (atomic number, Z) for the known isotopes reveals some insightful patterns. Such a plot, often referred to as a nuclide chart, is shown below. The black dots represent the stable isotopes. These stable isotopes are clustered along a slightly curved line known as the line of stability or band of stability.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Table_of_nuclides_(mul).svg

(edited slightly from original version)

A careful analysis of the graph and accompanying data leads to the following conclusions:

- For lighter elements (Z ≤ 16), the stability band follows a line with a slope of 1.0. That is, the ratio of neutrons to protons is about 1.0. This fits with some familiar elements like ...

- As atomic number increases past 16, the stability band veers away from the N = Z line. The ratio of neutrons to protons increases with increasing atomic number. As the nucleus grows in size, the number of neutrons required per proton increases. For heavier elements like lead (Pb), the neutron-proton ratio is ~1.5.

- There are certain specific numbers of protons or of neutrons that result in stable nuclei. These numbers, referred to as magic numbers, are 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82, and 126. Tin (Sn), with 50 protons, is a good example; it has 10 stable isotopes.

- More than half the stable isotopes have both an even number of protons and an even number of neutrons. There are only 4 isotopes with an odd number of protons and an odd number of neutrons. Stability seems to favor even numbers of each of the two nucleons.

- There are no stable nuclei with an atomic number of 83 or greater. The heaviest element with a stable isotope is lead. (Bismuth-209, with an atomic number of 83, is technically a radioisotope since it undergoes radioactive decay. Because its decay rate is incredibly low, some sources will regard it as a stable isotope.)

Predicting Decay Types

The nuclide chart we’ve included above is color-coded. The colors indicate the manner in which the radioisotopes are observed to decay. For instance, most radioisotopes located above the line of stability are colored blue. These isotopes have a neutron-to-proton ratio that is greater than that of stable isotopes of similar size. We could describe these radioisotopes as neutron-rich isotopes. As indicated on the chart, they decay by emitting a beta particle. During

beta decay, a neutron is converted to a proton while ejecting an electron. This has the effect of decreasing the neutron-to-proton ratio.

The radioisotopes located below the line of stability are colored orange. These isotopes have a neutron-to-proton ratio that is less than that of stable isotopes of similar size. We could describe these radioisotopes as proton-rich isotopes. As indicated on the chart, they decay by emitting a positron. During

positron decay, a proton is converted to a neutron while ejecting a positron. This has the effect of increasing the neutron-to-proton ratio. It is worth mentioning that

electron capture has this same effect.

Finally, the majority of the radioisotopes with an atomic number greater than 82 are colored yellow. These isotopes undergo

alpha decay. Alpha decay is most often observed of the heaviest of isotopes. Alpha decay releases a total of four nucleons and is the

quickest means of lowering nuclear mass. Many times, a single decay event will not be enough to attain stability; a series of consecutive decays is required to eventually reach a stable arrangement of nucleons with an atomic number of 82 or less. This is discussed in the next section - Nuclear Decay Series.

Nuclear Decay Series

Massive isotopes like uranium-238 typically undergo a series of consecutive decays before eventually achieving stability. This is known as a

decay series or a

decay chain. A common series of decays for U-238 includes:

α, β, β, α, α, α, α, α, β, β, α, β, β, α

(α = alpha decay, β = beta decay)

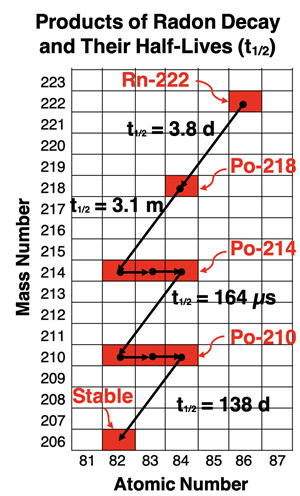

This series of decays can be represented on a plot of mass number (A) vs. atomic number (Z), beginning with the point where A = 238 and Z = 92. As seen on the graph, the decay series ends with Pb-206, a stable isotope of lead.

Uranium-238 is one of the more abundant radioisotopes that is naturally present in the Earth’s crust. Its decay series includes a variety of pathways with the above pathway being one of the more common ones. The individual decay steps in the chain each occur according to their own timeline. A half-life value (to be discussed in Lesson 2a) is the standard value for describing rates of decay. A daughter nuclei such as polonium-214 has a half-life if a few hundred microseconds and exists only briefly. On this timescale, any newly formed nuclei vanish so rapidly that the chain effectively ‘jumps’ to the next isotope. Other daughter nuclei, such as thorium-230, have longer half-lives (~75,000 years) and decay more slowly.

One of the daughter nuclei is

radon-222. It is the only gaseous radioisotope in the series. As a gas, it has the ability to migrate upward through the earth’s crust, seeping into groundwater and through foundation cracks, eventually entering buildings and homes. As a gas, it has a convenient means of entering the human body - we inhale it. The decay series continues after radon enters our lungs. The daughter nuclei in the remainder of the decay chain are solids that adhere to tissue in the lungs and airways. Polonium-218 and polonium-214 are intense alpha emitters with short half-lives. They rapidly decay, delivering a large dose of alpha particles to human tissue. Alpha particles have low penetration ability and are unable to penetrate our skin from the exterior. But once an alpha-particle emitter like radon gas enters our body, its high ionizing capability becomes problematic. This explains why radon gas is the #1 cause of lung cancer in non-smokers ... and of course, the #2 cause of lung cancer in smokers (as of this writing).

The Strong Nuclear Force

The Strong Nuclear Force

Given that more than 90% of all isotopes are radioactive, one may be tempted to ask

why are there so many unstable isotopes? But when you consider that the nucleus is closely-packed with like-charged protons that exert repulsive forces on one another, you may be more tempted to ask

why are there any stable isotopes at all? The stability of the nucleus is associated with the strong nuclear force. Let’s talk about it.

Many students are familiar with the jingle

opposite charges attract and like charges repel. This refers to the

electrostatic forces between charged particles or charged objects. In the nucleus, the charged particles are the protons. Protons repel each other and de-stabilize the nucleus. As more protons are added to the nucleus, there are more repulsive forces. While the strength of a repulsion decreases with distance, two protons separated by a neutron still experience a repulsive force. The electrostatic force extends to distances beyond the

nearest neighbor. For a large nucleus to be stable, it must somehow counteract repulsive forces that result from proton-proton repulsions.

The

strong nuclear force is an attractive force that exists between two adacent nucleons. Charge is not the basis for the strong nuclear force. Two protons attract. Two neutrons attract. A proton and a neutron attract. It is this attraction that holds the nucleus together despite the repulsive, electrostatice forces between protons. But there’s a catch. The strong nuclear force decreases in strength very rapidly with increasing distance; it vanishes at separation distances beyond a nucleon’s diameter. For all practical purposes, it only serves as an effective

nuclear glue for neighboring (touching) nucleons.

So what can a nucleus do to hold itself together as the proton-proton repulsions escalate with increasing atomic number? The answer is: add more neutrons. Neutrons do not electrostatically repel protons or other neutrons. A neutron will attract a neighboring neutron and a neighboring proton. Adding a neutron is a

repulsive-free means of increasing the attractions within the nucleus. So as the number of protons is observed to increase, the neutron-proton ratio is also observed to increase. The additional neutrons increase the strong nuclear force without contributing to the repulsive forces. It is in this sense that the neutrons are the

glue that hold the nucleus together.

Getting into the Weeds

There is always more to the story when it comes to nuclear chemistry. A proton and a neutron are not the most fundamental particles of nature. These nucleons are themselves composed of smaller particles known as quarks. In the standard model of matter, the quarks are called up quarks and down quarks. A proton is composed of two up quarks (+2/3 charge each) and one down quark (-1/3 charge), giving the proton an overall +1 charge. A neutron is composed of one up quark (+2/3 charge) and two down quarks (-1/3 charge each), making the neutron electrically neutral.

The quarks inside these nucleons are held together by the strong force. The strong force is a fundamental force of nature that is immensely strong at distances roughly equivalent to the size of a nucleon. The strong force is not confined to the nucleon’s perimeter, but leaks or spills out of the nucleon leading to a residual effect that we call the strong nuclear force. This strong nuclear force causes adjacent nucleons to attract each other and overcome the electrostatic repulsions.

Of course, there’s much more to the story ... and for the curious, a simple Google search will be the doorway to an endless amount of fascinating aspects of that story.

Before You Leave - Practice and Reinforcement

Now that you've done the reading, take some time to strengthen your understanding and to put the ideas into practice. Here's some suggestions.

- Try our Concept Builder titled Nuclear Decay. The third and final activity of the Concept Builder is a great follow-up to this lesson.

- The Check Your Understanding section below includes questions with answers and explanations. It provides a great chance to self-assess your understanding.

- Download our Study Card on Nuclear Stability. Save it to a safe location and use it as a review tool.

Check Your Understanding of Nuclear Stability

Use the following questions to assess your understanding. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

1. Identify the following statements as being TRUE or FALSE. For the false statement, identify what is wrong with it or correct the statement.

- The neutrons in the nucleus serve no function. They are insignificant particles that make an atom’s mass look bigger.

- Most isotopes of elements are stable. With the exception of the heavy elements, very few isotopes of an element are radioactive.

- A nucleus is most stable when the number of protons equals the number of neutrons.

- Scientists are uncertain regarding the role that neutrons play in an atom.

- All elements have both stable and radioactive isotopes.

- The number of neutrons in the nucleus is a random number and there is no predicting exactly how many will be present in a stable isotope.

- Protons outside the nucleus are positively charged. But in order for the nucleus to not explode due to repulsive forces, the protons inside it are electrically neutral.

2. Consider the following isotopes and their number of protons and neutrons. Based on the lessons learned from the nuclide chart, predict the most likely type of decay - beta (B), alpha (A), or positron (P) decay.

- Hydrogen-3 with 1 proton and 2 neutrons

- Carbon-14 with 6 protons and 8 neutrons

- Oxygen-14 with 8 protons and 6 neutrons

- Oxygen-20 with 8 protons and 12 neutrons

- Magnesium-28 with 12 protons and 16 neutrons

- Sulfur-40 with 16 protons and 24 neutrons

- Pb-214 with 82 protons and 132 neutrons

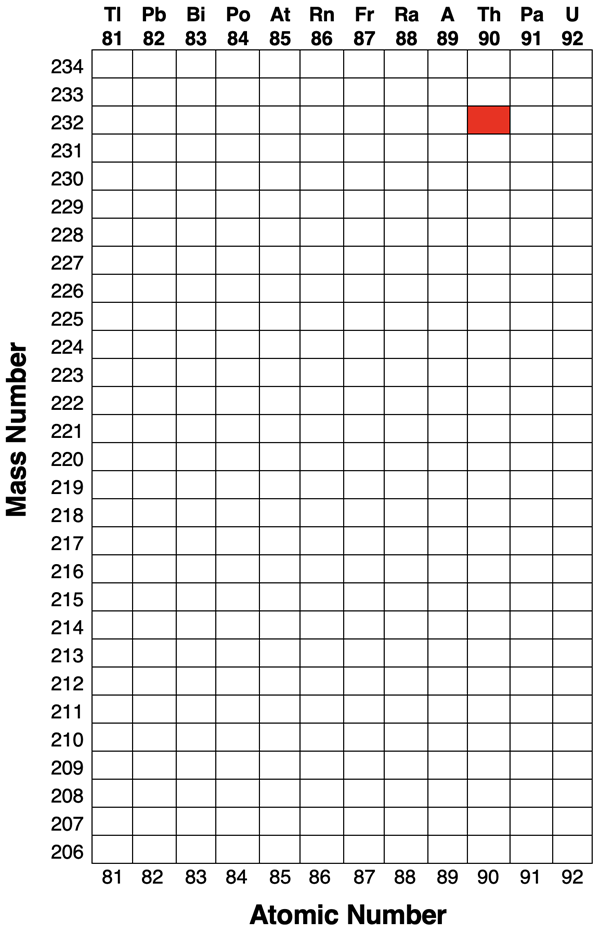

3. Thorium-232 is a radioisotope found in the Earth’s crust. It commonly decays as follows.

α, β, β, α, α, α, α, β, α, β

(α = alpha decay, β = beta decay)

On the provided graphic, show the individual decay steps and all daughter nuclei. Then complete the given paragraph:

a. The stable isotope in this decay series is named ___________________.

b. Alpha decay causes a change in the atomic # by _____ and a change in the mass # by _____.

c. Beta decay causes a change in the atomic # by _____ and a change in the mass # by _____.

d. Positron decay causes a change in the atomic # by _____ and a change in the mass # by _____.