Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Lesson 3: Nuclear Bombardment Reactions

Part b: Binding Energy

Part a:

Transmutation by Bombardment

Part b: Binding Energy

Part c:

Nuclear Fission and Fusion

The Big Idea

Binding energy is the energy that holds a nucleus together, arising from the strong nuclear force that overcomes repulsion between protons. The size of this energy—and the resulting mass defect—reveals how stable a nucleus is and why nuclear reactions release tremendous energy.

The Mass Defect

Protons and neutrons are the massive particles in the nucleus. When you add the masses of the neutrons and protons that are in any given nucleus and compare the sum to the actual mass of the nucleus, you will notice that they are different. The mass of the parts is not equal to the mass of the whole. The nucleus, with its bound nucleons (protons and neutrons), has less mass than its individual parts. The difference between the mass of the nucleus and its isolated protons and neutrons is referred to as the mass defect and represented by the symbol ∆m.

Protons and neutrons are the massive particles in the nucleus. When you add the masses of the neutrons and protons that are in any given nucleus and compare the sum to the actual mass of the nucleus, you will notice that they are different. The mass of the parts is not equal to the mass of the whole. The nucleus, with its bound nucleons (protons and neutrons), has less mass than its individual parts. The difference between the mass of the nucleus and its isolated protons and neutrons is referred to as the mass defect and represented by the symbol ∆m.

Mass defect = ∆m = Mass of nucleus - ∑mass of protons - ∑mass of neutrons

As defined by this equation, the mass defect is a negative value. That is, total system mass decreases as the nucleus forms from the isolated nucleons.

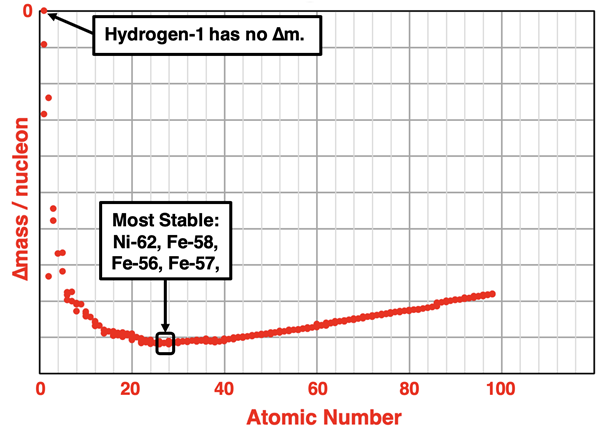

A mass defect is observed of all nuclei. The most stable nuclei have larger mass defects, meaning the ∆m value is more negative. The graph below shows the mass defect (on a per nucleon basis) for several hundred isotopes as a function of the atomic number. The curve starts at 0 (for the hydrogen-1 isotope, which is simply an unbound proton) and drops steeply into the negative area of the graph. The curve is relatively flat in the region between atomic numbers 24 and 40. The lowest points on the curve occur with atomic numbers of 25 (Mn), 26 (Fe), 27 (Co), and 28 (Ni). These are the most stable nuclei there are. And not surprisingly, the moons and planets of our solar system consist of cores made of an iron-nickel mixture, with the Fe-56 being the dominant isotope.

The idea that there is a loss of mass when a nucleus forms was at first bothersome to scientists. Doesn’t this violate the law of conservation of mass? And where did all this mass go? Does it just vanish?

Mass-Energy Equivalence Principle

In 1905, Albert Einstein proposed his special theory of special relativity. And with the theory, he introduced the mass-energy equivalence principle. Einstein showed that mass and energy are two connected forms of matter. Like two sides of the same coin, mass and energy can be thought of as the  same thing. What happens on one side of the coin happens on the other side of the coin. If a system loses energy, then the system loses mass. The more energy that is lost, the more the mass will be observed to decrease. And as always, the loss of energy in the system is matched by an equal amount of gain in energy by the surroundings.

same thing. What happens on one side of the coin happens on the other side of the coin. If a system loses energy, then the system loses mass. The more energy that is lost, the more the mass will be observed to decrease. And as always, the loss of energy in the system is matched by an equal amount of gain in energy by the surroundings.

Einstein’s principle encourages us to think in terms of mass-energy. The principle conveys that the missing mass in the system simply shows up as energy in the surroundings - usually as kinetic energy or radiation. Nothing disappears.There is still a balance - a mass-energy balance. The total amount of mass-energy in the universe stays constant; it is just shared differently between the nucleus (the system) and its surroundings.

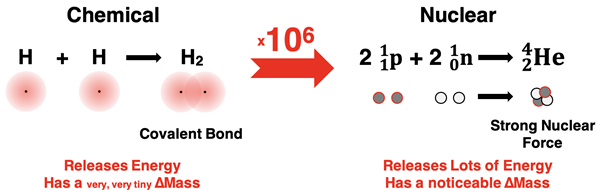

Nuclear changes are like chemical changes multiplied by ~106. For instance, let’s compare the formation of a hydrogen molecule from its atoms to the formation of a helium nucleus from its nucleons. We know there is an energy change occurring inside of each system because we observe an energy change in the surroundings. But there is a HUGE difference is in the amount. On a per gram basis, the formation of the nucleus releases about one million times more energy than the formation of the hydrogen molecule. And each change in energy is accompanied by a change in mass. For the chemical system, the ∆m is so tiny that mass appears to be conserved. So, when chemists analyze chemical changes, they think in terms of conservation of mass. Treating mass as conserved for a chemical change works for all practical purposes. But for the nuclear change, the ∆m is about one million times larger; it is large enough to measure. So, nuclear scientists think in terms of conservation of mass-energy, not mass alone.

E = mc2

You’ve heard it. You’ve seen it. It is a topic of memes and cartoons. You can find it on coffee cups and t-shirts. It’s the image on an occasional stamp. It’s iconic to science and math. It’s the infamous equation E = m•c2. It is Einstein’s expression of the Mass-Energy Equivalence principle.

You’ve heard it. You’ve seen it. It is a topic of memes and cartoons. You can find it on coffee cups and t-shirts. It’s the image on an occasional stamp. It’s iconic to science and math. It’s the infamous equation E = m•c2. It is Einstein’s expression of the Mass-Energy Equivalence principle.

When a nucleus is formed, there is a loss of energy by the system of particles as they arrange themselves to form the nucleus. This energy loss (measurable as an energy gain in the surroundings) is related mathematically to the mass defect. Thus, it can be stated that ∆Esystem = ∆msystem•c2 where c is the speed of light.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Binding Energy

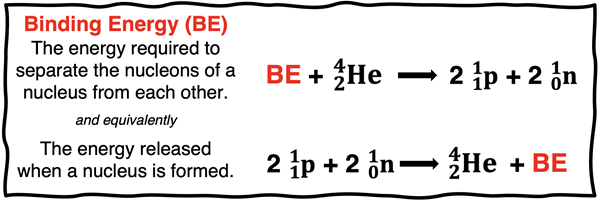

When two hydrogen atoms come together to form an H2 molecule, the chemical system loses energy as the covalent bond is formed. The lost energy of the system appears as gained energy in the surroundings. We refer to the change in energy as the bond energy.

Similarly, when nucleons (protons and neutrons) come together to form a nucleus, the nuclear system loses energy as the strong nuclear force holds the nucleons together. The lost energy of the system appears as gained energy in the surroundings. We refer to the absolute value of this change in energy as the binding energy of the nucleus. Though technically speaking, the binding energy is the energy change associated with the opposite process. It is defined as the energy required to separate the nucleons of a nucleus from each other. In one case - putting together the nucleus from its nucleons - energy is released and the ∆E is negative. In the other case - pulling the nucleus apart - energy is required and the ∆E is positive. The two E values are equal and opposite.

Binding Energy per Nucleon

A heavier nucleus has more nucleons and naturally, a greater binding energy. When comparing the binding energy of a light and a heavy nucleus, the heavy nucleus will win. But that’s an unfair competition if you wish to know in which case the individual nucleons are more tightly bound. It is customary to divide the binding energy by the number of nucleons, yielding a value which is a valid indicator of the how tightly each individual nucleon is bound. The binding energy per nucleon is the standard measure of the stability of a nucleus.

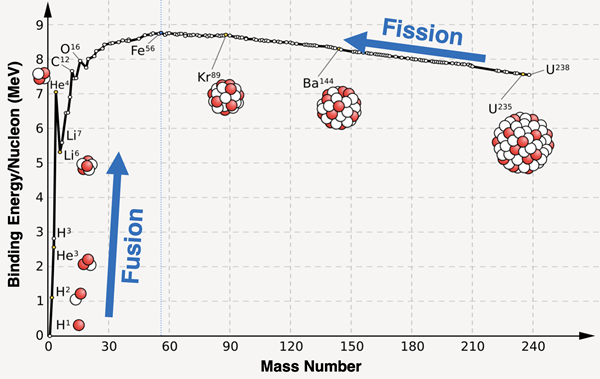

The graph below shows the binding energy per nucleon for several isotopes. As you would expect, the greatest binding energy is observed for the isotopes of iron and nickel, consistent with the findings of the mass defect/nucleon plot displayed earlier.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

Nuclear transmutations are driven by nuclear stability. That is, nucleons rearrange inside the atom so that the nucleon can attain a lower mass-energy state. A new nucleus with a greater binding energy per nucleon is formed. The individual nucleons are bound much tighter in this newly formed state. That’s stability!

Nuclear fission and nuclear fusion were two transmutation processes discussed in Lesson 3a. Nuclear fission involves the bombardment-induced splitting of a large nucleus (like U-235) to form two smaller nuclei (like Kr-89 and Ba-144).

These three isotopes are highlighted on the graph above. The two daughter nuclei - krypton-89 and barium-144 - have a greater binding- energy per nucleon that uranium-235. The 235 nucleons of uranium can achieve greater stability by undergoing fission into these two nuclei. For protons and neutrons, that’s a win! Heavier isotopes such as uranium tend to undergo fision to form two smaller isotopes located along the binding energy curve to the right of iron-56.

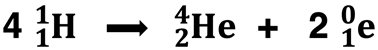

Nuclear fusion involves the combining of two or more lighter nuclei (like H-1) to form a heavier nucleus (like He-4). As discussed in Lesson 3a, solar fusion involves four hydrogen-1 nuclei fusing together to form a helium-4 nucleus and two positron particles.

These nuclei are also highlighted on the graph above. You will notice that helium-4 has a considerably greater binding energy than hydrogen-1 (a lone, unbound proton). Fusing four hydrogen nuclei results in greater stability. That’s another win! Lighter isotopes such as hydrogen tend to undero fusion to form isotopes that have a higher binding energy.

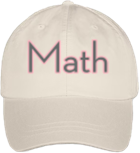

We will discuss fusion and fission in greater detail in Lesson 3c. But before we head onward to the next page, get out your math cap (and your calculator). Let’s learn how to do binding energy calculations!

Binding Energy Calculations

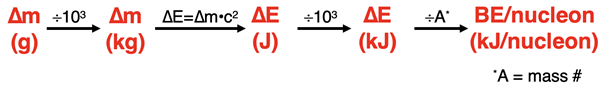

The binding energy can be determined using Einstein’s ∆E = ∆m•c2 equation. The value of c is 2.99792458 x 108 m/s. Knowing the mass defect (∆m) in kg allows one to calculate the energy change in Joule (J). The ∆E is expressed as J. The value is typically converted to kJ and then divided by the mass number (A, the number of protons plus neutrons) to determine the binding energy in kJ/nucleon.

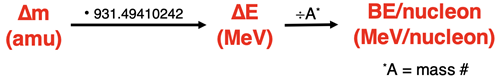

A more common approach is to calculate the ∆m in atomic mass units (amu) and to multiply by 931.49410242 to determine the energy change in the energy unit known as megaelectronvolts (abbreviated MeV). This second method relies on the fact that 1 amu•c2 is equivalent to 931.49410242 MeV. The ∆E is expressed as MeV per nucleus. Dividing this value by the mass number (A) yields the binding energy in MeV/nucleon.

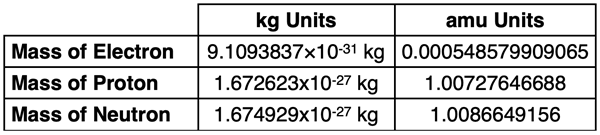

Mass values for hundreds of atoms can be found on the Binding Energy page of our Reference section of this Chemistry Tutorial. When used with the data in the table below, the mass defect (∆m) can be calculated.

Mass values of nuclei are calculated by subtracting the mass of all electrons in the atom from the mass of the atom. The mass defect is then calculated by subtracting the mass of all protons and neutrons from the mass of the nucleus. Use the absolute value of the result in subsequent calculations. One of the two flowcharts above will be useful in determining the binding energy/nucleon from the mass defect. Two worked-out examples are shown below. There is additional practice activities identified in the Before You Leave section.

Example 1 - Calculating the Binding Energy/Nucleon of Oxygen-16

The mass of an oxygen-16 atom (nucleus plus electrons) is 2.65601806 x 10-26 kg. (The value of c is 2.99792458 x 108 m/s.) Use this information to determine ...

- the mass of the nucleus (in kg)

- the mass of all protons and neutrons that are in the nucleus (in kg)

- the mass defect (in kg)

- the binding energy (in kJ)

- the binding energy/nucleon (in kJ/nucleon)

- the binding energy/nucleon in MeV/nucleon to 4 significant digits (Given: 1 MeV = 1.60 x 10-16 kJ)

Solution:

NOTE: We will save the rounding of numbers until the final calculation is performed.

m

nucleus = m

atom - m

electrons = 2.65601806 x 10

-26 kg - 8*(9.1093837×10

-31 kg)

m

nucleus = 2.656746811 x 10

-26 kg

m

all nucleons = 8*m

proton + 8*m

neutron = 8*(1.672623x10

-27 kg) + 8*(1.674929x10

-27 kg)

m

all nucleons = 2.6780416 x10

-26 kg

∆m = m

nucleus - m

all nucleons = 2.656746811 x 10

-26 kg - 2.6780416 x10

-26 kg

∆m = -2.12947893 x10

-28 kg

BE = ∆E = ∆m•c

2 = (2.12947893 x10

-28 kg) • (2.99792458 x 10

8 m/s)

2

BE = 1.913880217 x 10

-11 J = 1.913880217 x 10

-14 kJ

BE/nucleon = BE/(# nucleons) = 1.913880217 x 10

-14 kJ/16

BE/nucleon = 1.196175136 x 10

-15 kJ/nucleon

BE/nucleon = 1.196175136 x 10

-15 kJ/nucleon * (1 MeV/1.60 x 10

-16 kJ)

BE/nucleon = 7.476 MeV/nucleon

Example 2 - Calculating the Binding Energy of Iron-56

The mass of an iron-56 atom (nucleus plus electrons) is 55.93493633 amu. (1 amu•c

2 is equivalent to 931.49410242 MeV.) Use this information to determine ...

- the mass of the nucleus (in amu)

- the mass of all protons and neutrons that are in the nucleus (in amu)

- the mass defect (in amu)

- the binding energy (in MeV)

- the binding energy/nucleon (in MeV/nucleon) to 4 significant digits

Solution:

NOTE: We will save the rounding of numbers until the final calculation is performed.

m

nucleus = m

atom - m

electrons = 55.93493633 amu - 26*(0.000548579909065 amu)

m

nucleus = 55.92067328 amu

m

all nucleons = 26*m

proton + 30*m

neutron

m

all nucleons = 26*(1.00727646688 amu) + 30*(1.0086649156 amu)

m

all nucleons = 56.44913557 amu

∆m = m

nucleus - m

all nucleons = 55.92067328 amu - 56.44913557 amu

∆m = -0.52846229 amu

BE = ∆E = ∆m•c

2 = (0.52846229 amu) • (931.49410242 MeV/amu)

BE = 492.2595065 MeV

BE/nucleon = BE/(# nucleons) = 492.2595065 MeV/56

BE/nucleon = 8.790 MeV/nucleon

Before You Leave - Practice and Reinforcement

Now that you've done the reading, take some time to strengthen your understanding and to put the ideas into practice. Here's some suggestions.

- Our Calculator Pad section is the go-to location to practice solving problems. You’ll find plenty of Binding Energy practice problems on our Nuclear Chemistry page. Check out the following problem set: Set NC8: Mass Defect and Binding Energy.

- The Check Your Understanding section below includes questions with answers and explanations. It provides a great chance to self-assess your understanding.

- Download our Study Card on Binding Energy. Save it to a safe location and use it as a review tool.

Check Your Understanding of Binding Energy

Use the following questions to assess your understanding of concepts associated with mass-energy equivalency and binding energy. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

1. If energy is lost by the system when a nucleus is formed from its nucleons, then why is binding energy a positive value?

2. Explain what is meant by the phrase “nuclear changes are like chemical changes multiplied by ~10

6.”

3. The mass of a helium-4 atom (nucleus plus electrons) is 6.646479 x 10

-27 kg. (The value of c is 2.99792458 x 10

8 m/s.) Use this information to determine ...

- the mass of the nucleus (in kg)

- the mass of all protons and neutrons that are in the nucleus (in kg)

- the mass defect (in kg)

- the binding energy (in kJ)

- the binding energy/nucleon (in kJ/nucleon)

4. The mass of a lithium-7 atom (nucleus plus electrons) is 7.016003437 amu. (1 amu•c

2 is equivalent to 931.49410242 MeV.) Use this information to determine ...

- the mass of the nucleus (in amu)

- the mass of all protons and neutrons that are in the nucleus (in amu)

- the mass defect (in amu)

- the binding energy (in MeV)

- the binding energy/nucleon (in MeV/nucleon) to 4 significant digits