Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Lesson 3: Nuclear Bombardment Reactions

Part a: Transmutation by Bombardment

Part a: Transmutation by Bombardment

Part b:

Binding Energy

Part c:

Nuclear Fission and Fusion

The Big Idea

Transmutation by bombardment occurs when a nucleus is struck by a high-energy particle, triggering a nuclear reaction that transforms it into a different element or isotope. These reactions allow scientists to create synthetic elements and explore the limits of the periodic table.

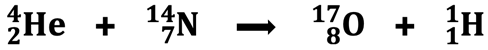

Nuclear Transmutation

We discussed radioactive decay in Lesson 1a. It is a spontaneous process in which a nucleus of a radioisotope releases a particle (alpha, beta, positron) and turns into a different nucleus. It is one of two types of processes that involve transmutation - the changing of one nucleus one element into another element. The other process is known as bombardment. Bombardment involves beaming a high-speed particle such as a neutron at a nucleus to cause that nucleus to undergo a transmutation. The first successful bombardment reaction was carried out by Ernest Rutherford in 1919. Rutherford bombarded nitrogen atoms with alpha particles and observed the formation of an oxygen nucleus.

We discussed radioactive decay in Lesson 1a. It is a spontaneous process in which a nucleus of a radioisotope releases a particle (alpha, beta, positron) and turns into a different nucleus. It is one of two types of processes that involve transmutation - the changing of one nucleus one element into another element. The other process is known as bombardment. Bombardment involves beaming a high-speed particle such as a neutron at a nucleus to cause that nucleus to undergo a transmutation. The first successful bombardment reaction was carried out by Ernest Rutherford in 1919. Rutherford bombarded nitrogen atoms with alpha particles and observed the formation of an oxygen nucleus.

This was the first occasion in which the nucleus of one element was changed into a nucleus of another element through artificial means. By bombarding a nucleus with a small particle, a new nucleus of a different element was formed! Ernest Rutherford, the “father of nuclear physics”, launched science into a new world of exploration - the world of bombardment reactions, particle accelerators, and the discovery of elements with atomic numbers greater than 92.

This was the first occasion in which the nucleus of one element was changed into a nucleus of another element through artificial means. By bombarding a nucleus with a small particle, a new nucleus of a different element was formed! Ernest Rutherford, the “father of nuclear physics”, launched science into a new world of exploration - the world of bombardment reactions, particle accelerators, and the discovery of elements with atomic numbers greater than 92.

Comic Source: Adventures Inside the Atom (Public Domain)

Bombardment Reactions

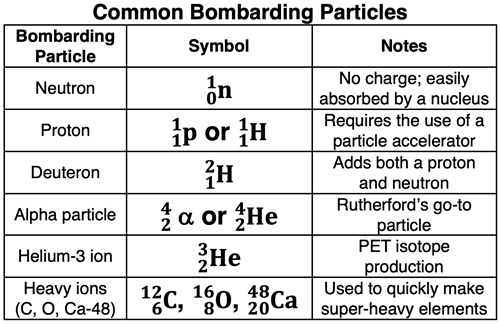

Radioactive decay occurs spontaneously. Alpha, beta, and positron emission involve one starting nucleus (a radioactive one), a product nucleus, and an emitted particle. Bombardment reactions involve a starting nucleus (often a stable one), a bombarding particle, a product nucleus (or two), and (often) another small particle. The bombarding particle might be a neutron, a proton, a deuteron, an alpha particle, or even heavier ions of carbon, oxygen, and calcium. The particle is accelerated to high speeds and beamed at the target nucleus.

Since Rutherford’s original bombardment finding, there have been a number of historically significant bombardment reactions. In 1931, James Chadwick bombarded a beryllium-9 nucleus with an alpha particle. The products were carbon-12 and a neutral particle with a mass similar to the proton. Chadwick had discovered the neutron.

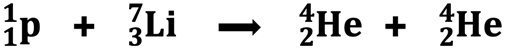

In 1932, John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton bombarded lithium-7 with a proton (hydrogen-1 nucleus) and observed the formation of two helium-4 nuclei. This was the first time that an atomic nucleus was split by bombardment into two smaller-massed nuclei, a process known as fission.

In 1933, Irene and Frederick Joliot Curie combarded aluminum-27 with an alpha particle and produced phosphorus-30. For the first time, a radioisotope (P-30) was produced by a bombardment reaction. Later in the century, nuclear bombardment would be used to produce radioisotopes of elements with an atomic number greater than 92.

Particle Accelerators

Particle Accelerators

Bombardment reactions require that the bombarding particle be accelerated to high speeds and directed or beamed at the target. With the exception of the neutron, the bombarding particles are positively charged and would be naturally repelled by the positively charged nuclei. For the particle to be captured by the target nucleus and lead to transmutation, its kinetic energy must be great enough to overcome the repulsive tendencies of like-charged particles.

Particle accelerators were developed to accelerate bombarding particles to high speeds. A particle source projects the charged bombardment particle into a long vacuum tube. A collection of fluctuating electric fields is used to increase the particle’s speed. If needed, magnets are used to direct the particle through the tube and at the target. An array of sophisticated detectors records the results of the high-energy collisions, allowing scientists to analyze the data and draw conclusions regarding the products of the bombardment reaction (if it occurs).

A Particle Accelerator

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Transuranium Elements

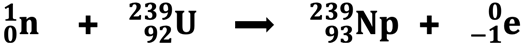

In 1940, uranium was the heaviest known element with an atomic number of 92. But that changed when Edwin McMillan and Phillip Abelson bombarded a uranium nucleus with a high-speed neutron. The product was neptunium-239 with an atomic number 93.

One year later, neptunium-239 was observed undergoing beta decay to produce plutonium-239 with an atomic number 94.

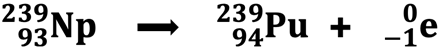

Neptunium and plutonium follow uranium on the periodic table. Np and Pu were named for the two planets that follow after Uranus, from which uranium was named. These elements were the first two of what was to eventually become 26 transuranium elements. Since their artificial synthesis by bombardment in the 1940s, trace amounts of neptunium and plutonium isotopes have been found as naturally occurring in uranium ore deposits. As of this writing, these are the only two of the 26 transuranium elements that have been confirmed to occur naturally. The remaining 24 transuranium elements are only artificially produced in nuclear laboratories by bombardment reactions.

Neptunium and plutonium follow uranium on the periodic table. Np and Pu were named for the two planets that follow after Uranus, from which uranium was named. These elements were the first two of what was to eventually become 26 transuranium elements. Since their artificial synthesis by bombardment in the 1940s, trace amounts of neptunium and plutonium isotopes have been found as naturally occurring in uranium ore deposits. As of this writing, these are the only two of the 26 transuranium elements that have been confirmed to occur naturally. The remaining 24 transuranium elements are only artificially produced in nuclear laboratories by bombardment reactions.

Source: https://sciencenotes.org/periodic-table-2017-edition-black-white/

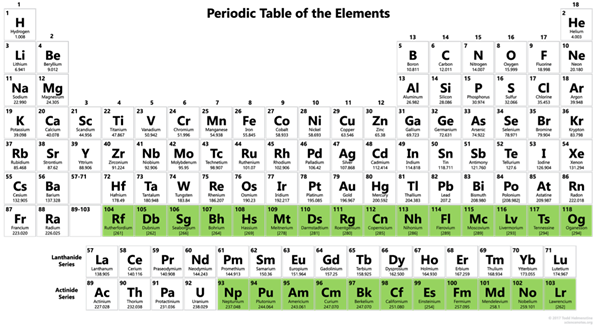

Only the lightest transuranium elements have practical applications. Plutonium, neptunium, americium, and curium provide nuclear fuel, deep-space power sources, neutron emitters, and usage in commercial smoke-detectors. Elements 97 through 103 are produced only in microscopic amounts (micrograms and picograms), have very short half-lives (seconds to hours), and are used solely for research into nuclear structure and the limits of the periodic table. The superheavy elements (SHEs) with atomic numbers 104 to 118 have short half-lives (milliseconds to minutes), are created atom-by-atom, and have no practical uses.

Nuclear Fission

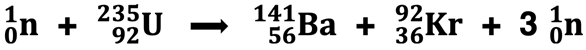

In 1938, German physicists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman bombarded a uranium-235 nucleus with a neutron, expecting to produce a transuranium isotope. To their surprise, the products were two nuclei that were lighter than uranium. Their findings showed that barium-141 and krypton-92 were the products. Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch provided the explanation of the science behind the bombardment reaction. The uranium atom was split into two smaller nuclei, while releasing some additional neutrons and lots of energy. Meitner and Frisch coined the term nuclear fission to describe the reaction. Nuclear fission soon became the foundation for nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons.

In 1938, German physicists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman bombarded a uranium-235 nucleus with a neutron, expecting to produce a transuranium isotope. To their surprise, the products were two nuclei that were lighter than uranium. Their findings showed that barium-141 and krypton-92 were the products. Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch provided the explanation of the science behind the bombardment reaction. The uranium atom was split into two smaller nuclei, while releasing some additional neutrons and lots of energy. Meitner and Frisch coined the term nuclear fission to describe the reaction. Nuclear fission soon became the foundation for nuclear reactors and nuclear weapons.

We will discuss nuclear fission in greater detail in Lesson 3c.

Nuclear Fusion

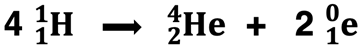

If nuclear fission is the splitting of a large nucleus into two smaller ones, then nuclear fusion can be thought of as being the opposite process. Nuclear fusion involves the combining of two smaller nuclei into a larger nucleus. Nuclear fission is artificially induced by neutron bombardment of uranium-235, with only a single instance of natural occurrence. But nuclear fusion occurs naturally in stars such as our sun. The sun is 73% hydrogen and 26% helium. The main source of energy in its core is the fusion of four hydrogen nuclei to form a helium nucleus and two positrons. The reaction occurs at a temperature of 14 million K.

If nuclear fission is the splitting of a large nucleus into two smaller ones, then nuclear fusion can be thought of as being the opposite process. Nuclear fusion involves the combining of two smaller nuclei into a larger nucleus. Nuclear fission is artificially induced by neutron bombardment of uranium-235, with only a single instance of natural occurrence. But nuclear fusion occurs naturally in stars such as our sun. The sun is 73% hydrogen and 26% helium. The main source of energy in its core is the fusion of four hydrogen nuclei to form a helium nucleus and two positrons. The reaction occurs at a temperature of 14 million K.

Fusion reactions require high pressure and high temperatures, an obstacle to mankind’s effort to replicate the process on Earth and harness its energy on a widescale basis. We will discuss nuclear fusion in greater detail in Lesson 3c.

Balancing Nuclear Equations Revisited

The balancing of nuclear equations was discussed in Lesson 1b. Now is an opportune time to review the principles of balancing equations and to apply them to bombardment reactions. The principles include the conservation of mass and the conservation of charge. Protons and neutrons give the nucleus its mass. The sum the protons and the neutrons is the mass number (A). The sum of all mass numbers is the same on the reactant and the product side, demonstrating the law of conservation of mass. Protons give the nucleus its charge (neutron have no overall charge). The atomic number (Z) identifies the number of protons and reflects the nuclear charge. The sum of the atomic numbers is the same on the reactant and the product side, demonstrating the conservation of charge.

The balancing of nuclear equations was discussed in Lesson 1b. Now is an opportune time to review the principles of balancing equations and to apply them to bombardment reactions. The principles include the conservation of mass and the conservation of charge. Protons and neutrons give the nucleus its mass. The sum the protons and the neutrons is the mass number (A). The sum of all mass numbers is the same on the reactant and the product side, demonstrating the law of conservation of mass. Protons give the nucleus its charge (neutron have no overall charge). The atomic number (Z) identifies the number of protons and reflects the nuclear charge. The sum of the atomic numbers is the same on the reactant and the product side, demonstrating the conservation of charge.

Problems in a typical chemistry course will follow one of two patterns.

- An incomplete nuclear equation is given with an unknown particle or nucleus and the problem involves determining the unknown. (See Example 1.)

- The bombardment reaction is described in words and the problem involves writing the symbols of all reactants and products. (See Example 2.)

The solution to both types of problems is modeled in

Example 1 and

Example 2 below. Additional practice is provided in the

Check Your Understanding section.

The task of completing or writing a complete nuclear equation involves the following steps.

- Write down the symbols of all known isotopes on the reactant side (target nuclei).

- Write down the symbols of all known particles on the reactant side (bombardment particles).

- Write down the symbols of all known isotopes on the product side.

- Write down the symbols of all known particles on the product side.

There is often an unknown particle or nucleus on the reactant or product side. Leave space for writing in its symbol once you have determined it. Conduct a mass balance and a charge balance to determine the A value (superscript) and the Z value (subscript) of any missing particle or nucleus. Once you known the A and Z values of the unknown, you can use a periodic table (for isotopes) to determine the elemental symbol or your understanding of particles to determine the particle symbol.

Example 1 - Completing a Nuclear Equation

Complete the following equations by determining the symbol for the missing nucleus or particle.

a.

b.

c.

Example 2 - Writing a Complete Nuclear Equation

Write complete nuclear equations that are consistent with the verbal description given of the bombardment reaction.

a. Hydrogen-2 ("deuterium") and hydrogen-3 ("tritium") collide in a bombardment reaction and undergo fusion to produce a helium-isotope and a neutron.

b. An iron-54 is bombarded with an alpha particle to give a proton and another nucleus.

c. An unknown nucleus is bombarded with an alpha particle to produce an oxygen-17 nucleus and a proton.

Next Up

Nuclear bombardment reactions are capable of releasing a large quantity of energy. You will learn why this is so and you will learn how to calculate the amount in

Lesson 3b. But before you leave, let’s take some time to internalize the concepts of this page using one or more of the suggestions in the

Before You Leave section.

Before You Leave - Practice and Reinforcement

Now that you've done the reading, take some time to strengthen your understanding and to put the ideas into practice. Here's some suggestions.

Check Your Understanding of Nuclear Bombardment

Use the following questions to assess your understanding of the various aspects of nuclear bombardment. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

1. Describe how bombardment reactions and radioactive decay are different.

2. Why are particle accelerators needed in bombardment reactions?

3. Americium-241 is bombarded with an alpha particle to produce two neutrons and another nucleus. Write the complete nuclear equation for this bombardment reaction.

4. A magnesium-26 nucleus is bombarded to produce a sodium-24 nucleus and an alpha particle. Write the complete nuclear equation for this bombardment reaction.

5. Technitium-99 (Tc) is bombarded with a positron to produce one new nucleus. There is no product particle. Write the complete nuclear equation for this bombardment reaction.