Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

A Look Back…A Look Forward

Imagine a girl riding a bicycle. As we've explored the chapters up to this point, we learned the physics that helps us describe the bike's position, velocity, and acceleration at different times. We've discovered that the bicycle can only speed up, slow down, or change direction when a force is applied. We've learned that the girl must do work on the pedals to give the bike kinetic energy. We've even encountered the physics of conservation of momentum that allows us to explain what happens if she collides with another bike!

We can explain so much of the 'how' and 'why' of the bike's motion using the physics that we've already encountered. The physics we'll explore in this chapter, however, will allow us to uncover another type of motion—rotational motion. What if, for example, we focused on the bicycle wheel itself? How might we describe its motion? What causes the wheel to speed up or slow down? Does something spinning in a circle have kinetic energy—even if it only spins in place? Our journey through this chapter on rotational motion will, in large measure, take us through the rotational version of each of the units we've explored up to this point. You see, nearly every quantity we learned about in prior chapters has a rotational counterpart that we'll explore in this chapter. What is really cool is that you'll see striking similarities between the rotational equations and their linear versions that we've already learned.

In this lesson, we'll begin by exploring rotational kinematics. We'll learn, for example, how we can describe the motion of the bicycle wheel as it spins about its own axis. We'll learn to describe this motion by determining an object's angular position, angular velocity, and angular acceleration. You'll see that it's like what we've already done…but with a new twist!

Angular Position and Angular Displacement

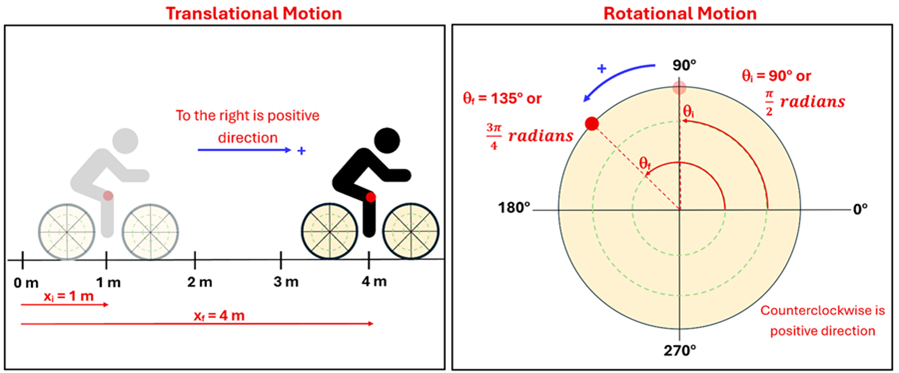

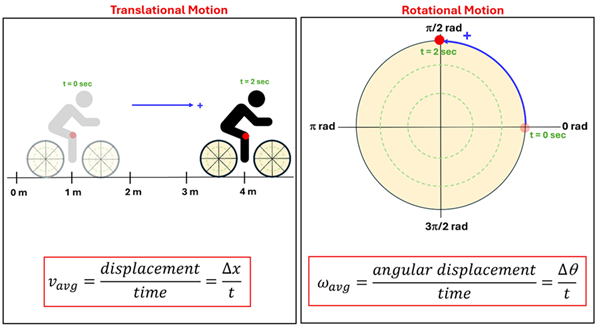

Imagine our bicycle wheel once again. Let's say the wheel is allowed to spin around an axle that is fixed in place. Now, imagine we stick a red dot on the rim of the wheel as shown below. With the help of a coordinate system, we can describe the angular position of that point on the wheel. Just like when we describe the position of a bike using a linear coordinate system, we can describe the position of the red dot on the rotating wheel using a polar coordinate system. Let's call the linear motion that we've already studied translational motion, that is, motion that gets us from one location to another along a line. We'll contrast this with rotational motion, that is, the motion of an object that spins about an axis.

As you look at the "Rotational Motion" picture above, can you see why we might describe the initial angular position of red dot on the wheel as θi = 90o? Physicists, like mathematicians, often make position measurements using the polar coordinate system with 0o along the +x-axis. We then measure positive angles counterclockwise from this reference line. If we spun the wheel to the new position shown in the figure, we would say that the final angular position is now θf = 135o relative to the coordinate system.

Although we measured these angular positions in degrees, physicists and mathematicians also like to describe the angular position in radians. So, it would be equivalent to say that the initial angular position of the red dot was π/2 radians, but the final angular position is now 3π/4 radians.

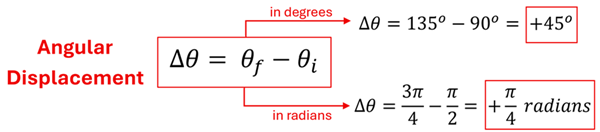

The angular displacement, ∆θ, is merely the change in angular position. In other words, it's how many degrees (or radians) the dot rotated. We can find the angular displacement like this:

Like its translational counterpart, angular displacement is a vector. We would say that the angular displacement is +45o or 45o counterclockwise (CCW). This is to distinguish it from moving 45o in the clockwise (CW) direction.

Example 1: Finding Angular Displacement

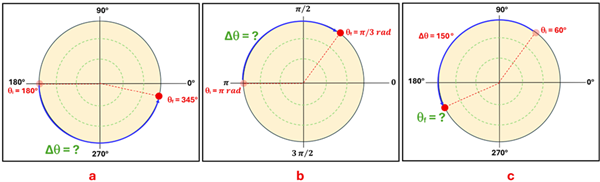

Problem: Find the angular quantity identified for each situation.

Solution: (a) ∆θ = 345o – 180 o = +165 o. (b) ∆θ = π/3 - π = -2π/3 rad. (c) θf = ∆θ + θi = 150 o + 60 o = 210 o.

Example 2: Different Radii

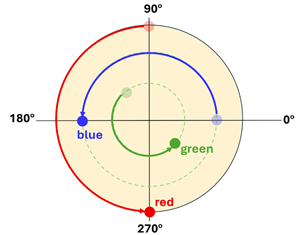

Problem: Three colored dots are each fixed to a wheel and the wheel is allowed to rotate. Which dot experienced the greatest angular displacement?

Solution: All three have the same angular displacement. It is true that the red ball traveled further along its arc compared to the blue and green dots. However, angular displacement is concerned with the angle traced out. Each of these dots has the same angular displacement of +180 o.

What's the Big Deal with Radians?

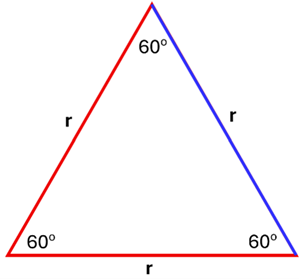

While we'll use both degrees and radians to describe the angular displacement of a rotating object, there are reasons why many physicists and mathematicians prefer radians. But why? To help us understand, imagine an equilateral triangle with each side equal to length 'r' and each angle 60o. All three sides are identical in length, but we've colored two of the sides red and one side blue.

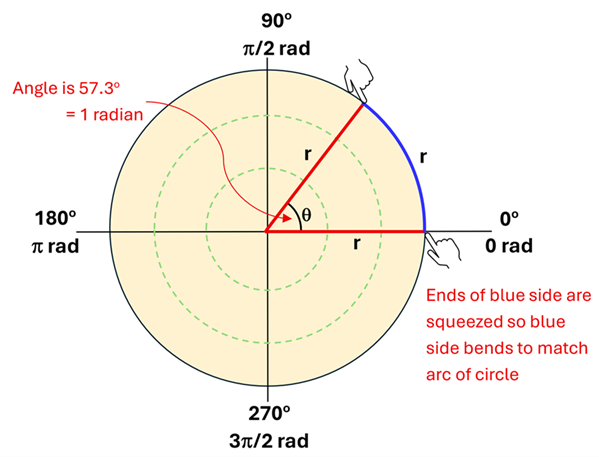

Now, imagine that we place this equilateral triangle on our polar coordinate system and we push the two ends of the blue side of the triangle so that it curves just enough to trace out an arc of the circle. Notice that the two red sides make up the radius of the circle shown, while the blue side—which is now curved—traces out an arc along the circumference of the circle.

Since we had to push the two ends of the blue side to get it to curve along the arc of the circle, the angle formed between the two red sides is now a little less than 60o. In fact, it is 57.3o. We give this angle a special name. We call it 1 radian.

1 radian is the angle formed when the arc length is equal to the radius.

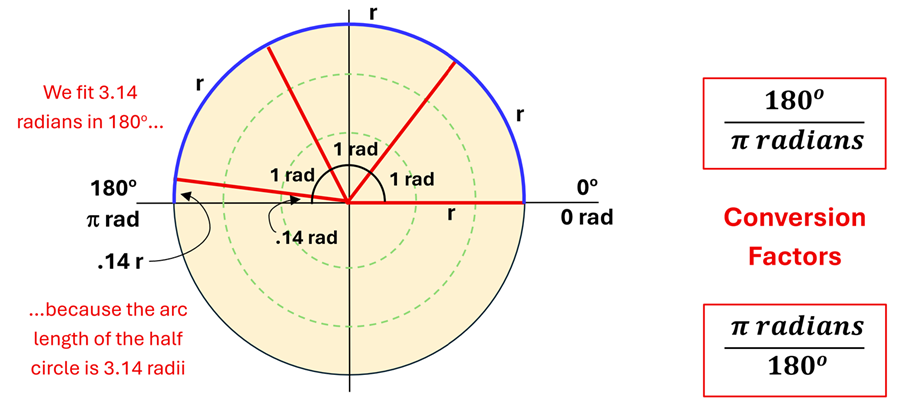

We can see from the figure below that we can fit 3.14 radians into 180o. Said another way, the arc length for half a circle is 3.14 radii. Pretty cool, huh?! Therefore, we have a convenient ratio that will allow us to convert from radians to degrees…or degrees to radians.

It is no coincidence that the word 'radian' sounds like 'radius.' We can see from our equilateral triangle example this significant connection. Because of this, we'll see that the biggest reason why radians are so convenient is that they allow us to go back and forth between an angular quantity and its corresponding linear quantity. This is what we'll explore in the next lesson. For now, however, let's try a couple of examples to make sure we can change from degrees to radians and vice versa.

Example 3: Degrees to Radians

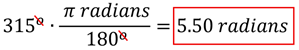

Problem: A spinning wheel has an angular displacement of 315o. What is its angular displacement in radians?

Solution: Since we want degrees to cancel out, we'll use the conversion factor with degrees on the bottom. This gives us an angular displacement of 5.50 radians.

Example 4: Radians to Degrees

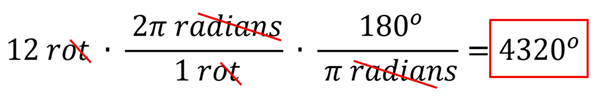

Problem: When turned off, a potter's wheel makes 12 complete rotations before coming to rest. If each rotation traces out 2π radians, how many degrees does the potter's wheel turn before coming to rest?

Solution: First, we need to recognize that the angular displacement for 12 rotations will be 24π radians. Then, since we want radians to cancel out, we'll use the conversion factor with radians on the bottom. The potter's wheel will turn through an angle of 4320o before coming to rest.

Angular Velocity

Think back to our bicycle example at the beginning of this lesson. Just like we can describe the average velocity (vavg) of a moving bike as its displacement (or change in position) over time, we can describe a rotating object's average angular velocity (ωavg) as its angular displacement (or change in angular position) over time. If a rotating object spins counterclockwise, we'll say that its average angular velocity is positive. If it spins in the clockwise direction, we'll say that it is negative.

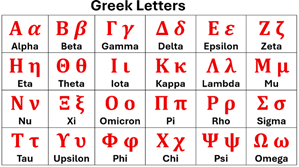

While we typically use letters from the Latin alphabet (a, b, c…) as variables when describing translational quantities, you may have noticed that we borrow letters from the Greek alphabet (alpha, beta, gamma…) for our variables that describe rotational quantities. This is a convenient way to keep these straight. We've already used θ and ω, but there are many more we'll use in the lessons ahead.

Here are a couple of examples to give you a chance to practice finding an object's average angular velocity. Give them a whirl!

Example 5: A Constant Angular Velocity

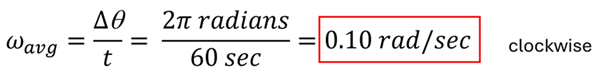

Problem: Find the average angular velocity (in rad/sec) of the second hand on a clock.

Solution: The second hand on a clock has an angular displacement of 2π radians in 60 seconds. Thus, the magnitude of the average angular acceleration is 0.10 rad/sec. Since we typically define counterclockwise as the positive direction, the average angular velocity will be -0.10 rad/sec or 0.10 rad/sec clockwise.

Example 6: A Changing Angular Velocity

Problem: The data table below shows the angular position of a red dot on the rim of a counterclockwise spinning wheel over a time of 5 seconds. Determine the average angular velocity over this 5-second interval.

| Time (sec) |

Angular Position (rad) |

| 0 |

3 |

| 1 |

15 |

| 2 |

26 |

| 3 |

36 |

| 4 |

45 |

| 5 |

53 |

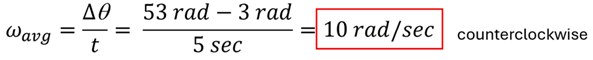

Solution: The average angular velocity over the 5-second interval is +10 rad/sec.

You might have noticed from the data table that the spinning wheel in Example 6 slowed down over time. We were able to use the above equation to find the average angular velocity over the 5-second interval, but how would we find the instantaneous angular velocity—the angular velocity at any one moment in time?

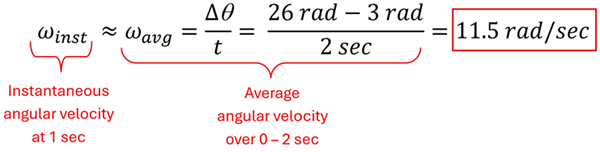

Let's say, for example, we wanted to know the instantaneous angular velocity at 1 second. One way of doing this is to pick a time right before and right after and find the ratio of the change in angular position over this small amount of time. The average angular velocity over a small enough interval is likely very close to the instantaneous angular velocity at the midpoint time.

Another way to find the instantaneous angular velocity, however, is to know something about the rate at which the rotating object is changing its angular velocity. That brings us to the concept of angular acceleration--the final concept we'll tackle in this section.

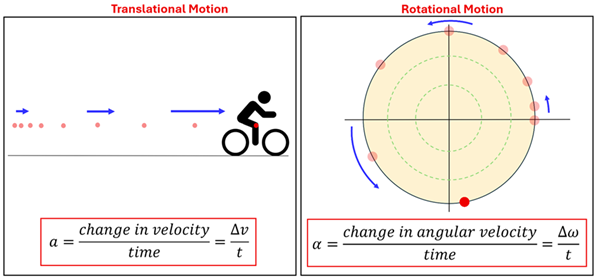

Angular Acceleration

Like its counterpart in translational motion, angular acceleration (a) is the rate at which a rotating object changes its angular velocity. If a rotating object's angular velocity is constant, then we say that there is no angular acceleration. If, however, the object's angular velocity increases or decreases with time, the object will have an angular acceleration. You might have guessed that we have a way to calculate an object's angular acceleration that is remarkably similar to that of an object's translational (or linear) acceleration. You might also have guessed that we'd pick another Greek letter to represent angular acceleration.

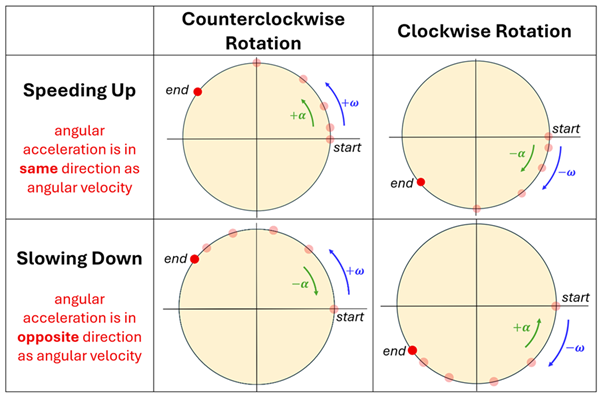

We saw in our lesson on acceleration back in 1-D Kinematics that acceleration is also a vector quantity. What makes the direction of acceleration tricky, however, is that it is not necessarily the same as the direction of the object's velocity. The same is true with angular acceleration. Consider these four cases in which a red dot on a wheel's rim is shown at one-second intervals. This may help you wrap your mind around when the angular acceleration is considered positive and when it is negative.

Example 7: Finding Angular Acceleration

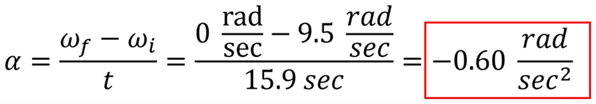

Problem: Consider again the potter's wheel from Example 4. When turned off, the potter's wheel was traveling counterclockwise at 9.5 rad/sec. The wheel came to rest after 15.9 sec. Provided it slows down at a constant rate, what is the angular acceleration of the wheel?

Solution: Using the angular acceleration equation, we find the acceleration to be -0.60 rad/s2. It is negative because, although the wheel is spinning in the counterclockwise direction, the angular acceleration is in the clockwise direction. What we've calculated here is technically the average angular acceleration. Since the wheel slowed at a constant rate, however, the average angular acceleration will be the angular acceleration at any instant when it was slowing down. In this chapter, we will limit our study to cases where the angular acceleration is constant.

Just like our study of 1-D kinematics led us to an understanding of displacement, velocity, and acceleration, our study of rotational kinematics has begun with us exploring angular displacement, angular velocity, and angular acceleration. But are these translational quantities in some way connected to their rotational counterparts? Is there a way to describe these translational quantities for an object that is undergoing rotational motion? The answer is 'yes,' and that is what we'll explore in the next section.

Check Your Understanding

Use the following questions to assess your understanding. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

1. What is the angular displacement and average angular velocity over the 8-second interval in each situation (A and B)?

2. Convertt the following...

(A) ____ radians = 60.0o

(B) ____ radians = -72.0o

(C) 1.00 Radians = ___o

(D) 2π radians = ____o

3. To heat food evenly, a motor in most microwaves turns a plate in a complete counterclockwise circle once every 30 seconds.

(A) Through what angle (in degrees) did the plate turn in this period of time?

(B) Through what angle (in radians) did the plate turn in this period of time?

(C) What is the average angular velocity (in degrees/sec) of the plate?

(D) What is the average angular velocity (in radians/sec) of the plate?

(E) If the angular velocity was constant during the plate's rotation, what was its angular acceleration?

4. When turned to its 'highest' setting, a fan rotates at 250 radians/sec. When it is turned on, it takes 8.0 seconds to get up to this angular velocity. When turned off, it takes 14.0 seconds to slow down and stop.

(A) While speeding up, what is the average angular acceleration (in rad/s2)?

(B) While slowing down, what is the average angular acceleration (in rad/s2)?

5. A carousel is a popular ride at carnivals. When the carnival worker starts the ride, the carousel begins from rest and speeds up with an angular acceleration of 4.5o/s2. It takes 8.0 seconds to get to its maximum angular velocity.

(A) What is its maximum angular velocity?

(B) At this angular velocity, how much time does it take for a rider to make one complete revolution?

Person on bike icon used throughout modified from MS Word Icons

Hand pointing icon used in some image from MS Word Icons

Figure 1 from MS Word

Figure 2 Picture borrowed from Wikimedia Commons (From Kritzolina) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pottery_at_the_Chokhi_Dhani_Resort_Panchkula_24.jpg under license Creative Commons

Figure 3 from MS Word Stock Images

Figure 4 Picture borrowed from Wikimedia Commons (From Norbert Nagel) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carousel_La_Belle.jpg under license Creative Commons