Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

A Wheel with Many Speeds

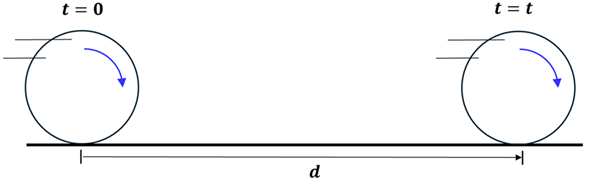

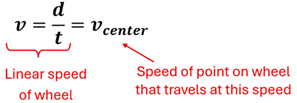

You are asked to find the speed of a wheel as it rolls across the floor. You might say, "That’s easy. I just need to find out how far it travels in a given amount of time and divide these (v=d/t) to get its speed."

On the one hand, you’re right. You’ve found the translational (linear) speed of the wheel. But isn’t the wheel also rotating? Does that matter?

In reality, the wheel has many velocities at the same time. In fact, every point on the wheel is moving with a different velocity! Understanding how each point on the wheel can have a different velocity will help us make sense of how a wheel rolls. That is the goal of this section.

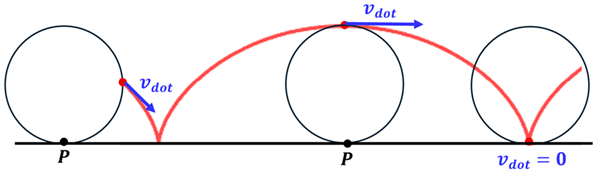

Let’s take a deeper look at rolling by putting a red dot at one point fixed on the rim of the wheel. Let’s watch as this dot traces out its motion over time as the wheel rolls. The below animation may be helpful to help you visualize how the path of this red dot is formed.

At any moment, the wheel is in contact with the floor at just one point. Let’s call point P the point on the wheel that is in contact with the floor. We can see, however, that with each new moment, point P is a new point on the wheel. In other words, point P is not fixed to the wheel but instead changes as the next point on the wheel touches the floor with each fraction of a turn. By analyzing the path of the red dot carefully, we can recognize that point P is actually at rest with respect to the floor. It must be since, when the red dot becomes point P, we can see that the velocity changes direction from downward to upward. That must also mean that as the red dot makes its way around the rolling wheel, it takes on different velocities.

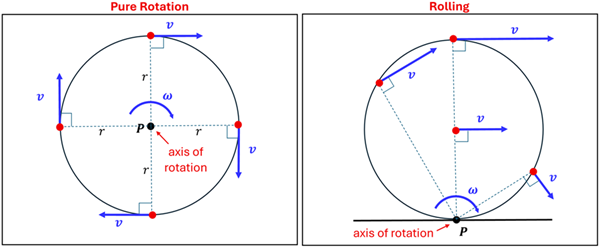

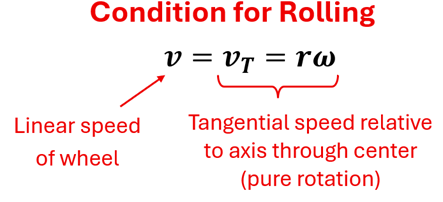

We saw in a previous second of this lesson that every point on the edge of a rotating object has a tangential velocity that is perpendicular to the radial distance from the axis of rotation. In fact, we saw that this tangential velocity increases as the radius from the axis of rotation increases according to the equation v = r ω, where ω is the angular velocity. Consider the picture below:

On the left is labeled “Pure Rotation.” Since every point on the wheel is spinning with the same ω, and since every point on the rim of the wheel is the same distance r from the axis of rotation, we can see why every point must have the same speed. Only the direction is different. Now, imagine that the axis of rotation was not the center of the wheel but instead the very bottom of the wheel, as illustrated with the right picture labeled "Rolling." Every point on this wheel is now rotating with the same angular velocity ω about point P. However, since each point on the rim of the wheel is a different distance from the axis of rotation, they will have different speeds in addition to moving in different directions. In fact, this is true not just for points on the rim of the wheel, but for any point on the wheel. We can see this by considering the point located at the very center of the wheel. Comparing the point at the very top of the wheel with this point at the center, we can see that both points have a velocity to the right, but that the point at the top is actually traveling twice as fast as the point in the center. This occurs since the top of the wheel is twice as far from point P (the axis of rotation). In addition, since the point of the wheel in contact with the floor is zero distance from the axis of rotation, it must not have any velocity. Thus, every other point on the wheel is actually rotating about the wheel’s point of contact with the floor.

The 'Rolling Equation'

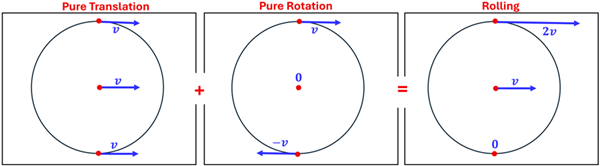

There is still another helpful way to understand how rolling works. Let’s consider a wheel experiencing three kinds of motion. First, let’s consider pure translation. If a wheel were to experience pure translation, then every point on the wheel would be moving to the right with the same velocity v . This might occur if the wheel is sliding across a frictionless surface (maybe across the ice) where it is not rotating at all. Second, let’s consider pure rotation. This is the type of motion we’ve explored where a wheel spins about a fixed axis through its center. Let’s also say that this wheel is spinning with just the right angular velocity so that every point on its rim has a tangential velocity equal to v —the same v as in the case of pure translation. The third type of motion, rolling, is then simply a combination of translation plus rotation happening simultaneously.

This is another way to explain why the point where the wheel is in contact with the floor is actually at rest, while the velocity of the top of the wheel is twice the velocity of the center of the wheel. And while we illustrated this ‘rolling equation’ for just three points in our figure above, we would see that this addition of the vector velocities at any point would give us the rolling wheel’s velocity at that point. The below animation may be helpful in seeing what we mean when we say:

Pure Transitional + Pure Rotation = Rolling

You may have caught the one condition that we said must be satisfied for this ‘rolling equation’ to hold true. We said that for the pure rotation part of our equation, the wheel must spin at just the right angular velocity such that the tangential speed at its rim matches the pure translation (linear) speed. This condition actually helps us connect the linear speed of the wheel to the rate at which the wheel rotates.

If we simply performed the calculation of dividing the distance the wheel rolled along the ground by the time to travel that distance (v=d/t) referenced at the start of this section, what point on the wheel actually has this speed? It turns out that this is the speed of the point at the very center of the wheel. In other words,

Let’s see if we can make sense of what we’ve learned by considering the example below.

Example 1: Finding the Speed of a Wheel

Problem: The tires on a truck are rolling as the truck travels down the road at a constant speed of 20 m/s. The radius of each tire is 0.25 m.

(A) What is the tangential speed of a point on the edge of the tire with respect to the axle?

(B) What is the angular speed of the tire relative to the axle?

(C) What is the speed of the bottom of the tire relative to the ground?

(D) What is the speed of the top of the tire relative to the ground?

Solution:

(A) Since the wheel is rolling, we saw above that the linear speed of the truck must be equal to the tangential speed of the wheel relative to the axle. Thus, vT = 20 m/s relative to the axle.

(B) To find the angular speed, we’ll use our link equation and get 80 rad/s.

(C) vbottom = 0 m/s

(D) vtop = 40 m/s.

Experiencing Friction Without Losing Energy

We might ask, "What causes the wheel to roll in the first place? Why doesn’t it just slide across the floor without spinning?" Friction is the answer. More specifically, it’s static friction between the floor and the wheel that allows the wheel to roll. We might also ask, "If friction acts on the wheel, then how come a wheel can continue to roll for great distances? After all, when a car skids, it is friction that causes the car to stop, right?!" We can understand the difference between skidding and rolling as we remember that there is both sliding friction and static friction. When a car skids, the wheels 'lock up' and thus the force of friction (in this case sliding friction) acts over the distance that the car skids. In Lesson 2 of the chapter on Work and Energy, we saw that in this case friction does negative work on the wheel causing the car to lose kinetic energy and slow down. In the case of rolling, however, the point on the wheel in contact with the ground is actually at rest with respect to the ground. As a result, the force of friction (in this case static friction) doesn’t act over a distance but merely keeps that point momentarily at rest. Recall that a force must act over a distance in order for that force to do work on an object. The result is that in the case of rolling, no work is done by friction and thus no energy is lost. The wheel continues to roll for a long, long time.

In reality, even a rolling wheel will eventually stop. As it turns out, no wheel really touches the ground at a single point. Because of the weight of the wheel (and of the car that it might be holding up), the wheel is in contact with the ground over a small region in front of and behind the ideal point where the wheel makes contact with the ground. This is sometimes called rolling friction. Rolling friction comes about because of the deformation of both the rolling object (the wheel) and the surface it is rolling on (the ground), as well as slippage between these two. This deformation causes a small loss of energy since negative work is being done on the wheel due to sliding friction.

In recent years, anti-lock braking systems (ABS) have become standard in all cars. When a driver pushes on the brakes, the car detects that the wheel is skidding and that sliding friction is the type of friction the tire is experiencing. Back in our chapter on Newton's Laws we discussed that the coefficient of sliding friction is typically less than the coefficient of static friction. Thus, ABS brakes 'pump' several times a second in an effort to recreate a situation where the rolling tire takes advantage of static friction instead of sliding friction to offer a greater amount of friction and stop the car sooner.

Check Your Understanding

Use the following questions to assess your understanding. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

1. Identify each statement as True or False for a wheel that rolls along the ground.

(A) Different points on the wheel are traveling at different speeds.

(B) Each point on the wheel is rotating about the bottom of the wheel (where it makes contact with the ground).

(C) The top of the wheel is the point on the wheel that travels the slowest.

(D) The velocity of any point on the wheel is directed perpendicular to a line connecting the bottom of the wheel and that point.

2. A Wheel is rolling across the floor. For the five points identified on the wheel, rank these in terms of their speed (from greatest speed to least speed) relative to the ground.

3. The 70.0 cm diameter wheel on a bicycle rolls on the road as it rotates with an angular speed of 43 rad/s.

(A) What is the linear speed of the bike with respect to the road?

(B) What is the speed of the bottom of the wheel with respect to the road?

(C) What is the speed of the top of the wheel relative to the road?

4. Select the type of friction (static or sliding) that applies to each situation.

(A) A bicycle rider slams on the brakes, locking the wheels until the bike comes to a stop.

(B) A bicycle rider coasts as the bike rolls smoothly down the road.

Figure 1 Picture borrowed from Wikimedia Commons (From Zorgit) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cycloid_f.gif under license Creative Commons

Figure 2 Picture borrowed from Wikimedia Commons (From Rulerole) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rolling_animation.gif under license Creative Commons