Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Lesson 2: Galvanic Cells

Part a: What is a Galvanic Cell?

Part a: What is a Galvanic Cell?

Part b:

Reduction Potentials

Part c:

Cell Voltage

Part d:

Batteries and Commercial Cells

The Big Idea

Galvanic cells operate because oxidation and reduction occur in separate locations, forcing electrons through an external circuit. This page explains the roles of the anode, cathode, and the salt bridge and discusses the various ways of representing a galvanic cell.

Electrochemical Cells

Electrochemistry is the study of the interaction between electrical energy and chemical reactions. Some chemical reactions can cause the flow of electrons and a sustained electric current. And other chemical reactions occur because of the flow of electrons in the form of a sustained electric current. These reactions and their applications will be the focus of Lesson 2 and Lesson 3 of this Tutorial chapter.

Electrochemistry is the study of the interaction between electrical energy and chemical reactions. Some chemical reactions can cause the flow of electrons and a sustained electric current. And other chemical reactions occur because of the flow of electrons in the form of a sustained electric current. These reactions and their applications will be the focus of Lesson 2 and Lesson 3 of this Tutorial chapter.

In Lesson 2, we will study a type of electrochemical cell known as a galvanic cell (sometimes referred to as a voltaic cell). A galvanic cell is reliant upon a spontaneous redox reaction. The reaction occurs naturally. As it does, electrical energy is generated.

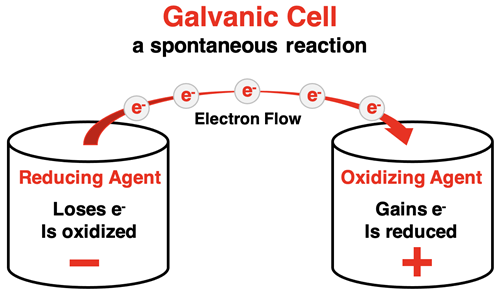

All electrochemical cells utilize oxidation-reduction reactions. These redox reactions involve the transfer of electrons. One substance loses electrons and is oxidized. The other substance gains the lost electrons and is reduced. There can’t be an oxidation half-reaction without a reduction half-reaction. The connection between the two halves are the electrons.

A galvanic cell takes advantage of this fact by placing the reducing agent (substance being oxidized) in a separate compartment than the oxidizing agent (substance being reduced). The electrons that are lost in the oxidation move through a wire from one compartment to the other compartment where the reduction occurs. This movement of electrons can do useful work. It can light a light bulb, start a car engine, operate a mobile phone, and more.

The Zn-Cu2+ Cell

If a strip of zinc metal is placed in a solution containing copper(II) ions, a spontaneous oxidation-reducation reaction occurs. As time elapses, the blue-ish solution gradually fades in color and a reddish-brown flakes begin to form on the zinc strip. The blue is a sign of Cu2+ ions. The reddish-brown flakes are solid copper. The Cu2+ ions are gaining electrons and turning into Cu(s). This reaction occurs on the surface of the zinc strip where the Zn(s) is losing two electrons and turning to Zn2+ ions.

If a strip of zinc metal is placed in a solution containing copper(II) ions, a spontaneous oxidation-reducation reaction occurs. As time elapses, the blue-ish solution gradually fades in color and a reddish-brown flakes begin to form on the zinc strip. The blue is a sign of Cu2+ ions. The reddish-brown flakes are solid copper. The Cu2+ ions are gaining electrons and turning into Cu(s). This reaction occurs on the surface of the zinc strip where the Zn(s) is losing two electrons and turning to Zn2+ ions.

Cu2+(aq) + Zn(s) → Cu(s) + Zn2+(aq)

The zinc metal is oxidized and the copper ions are reduced. It’s a beautiful reaction to observe ... but it otherwise falls far short of being useful. Let’s try the reaction a different way.

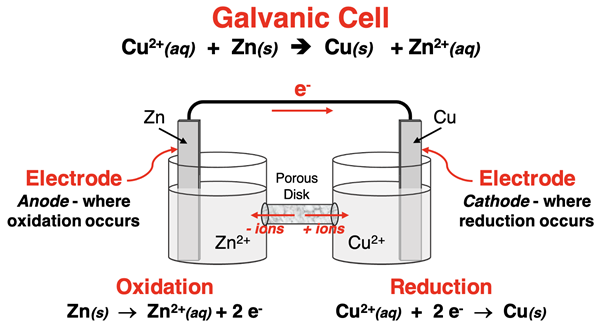

Let’s separate the Zn strip from the Cu2+ ions and place them in separate compartments. This creates a galvanic cell. The two compartments are called half-cells. Every galvanic cell is composed of two half-cells. A half-reaction - an oxidation or a reduction - occurs in each half-cell. The Zn(s) is the reducing agent. It is oxidized and loses two electrons. The Cu2+(aq) is the oxidizing agent. It is reduced and gains two electrons. But we need a way to get the electrons to move from the Zn in one half-cell to the Cu2+ ions in the other half-cell. So, we insert an electrode in each half-cell and connect the electrodes by a wire. An electrode is a conductive solid that acts as a surface upon which electrons are exchanged with the aqueous solution. The zinc strip and a copper strip serve as useful electrodes for this reaction. Electrons will move from the compartment where oxidation occurs to the compartment where reduction occurs. Upon arrival in the Cu | Cu2+ compartment, electrons move from the copper strip to the Cu2+(aq) ions that surround the electrode. The ions are reduced and Cu(s) forms on the copper electrode. The diagram below depicts the anatomy of this galvanic cell.

Let’s separate the Zn strip from the Cu2+ ions and place them in separate compartments. This creates a galvanic cell. The two compartments are called half-cells. Every galvanic cell is composed of two half-cells. A half-reaction - an oxidation or a reduction - occurs in each half-cell. The Zn(s) is the reducing agent. It is oxidized and loses two electrons. The Cu2+(aq) is the oxidizing agent. It is reduced and gains two electrons. But we need a way to get the electrons to move from the Zn in one half-cell to the Cu2+ ions in the other half-cell. So, we insert an electrode in each half-cell and connect the electrodes by a wire. An electrode is a conductive solid that acts as a surface upon which electrons are exchanged with the aqueous solution. The zinc strip and a copper strip serve as useful electrodes for this reaction. Electrons will move from the compartment where oxidation occurs to the compartment where reduction occurs. Upon arrival in the Cu | Cu2+ compartment, electrons move from the copper strip to the Cu2+(aq) ions that surround the electrode. The ions are reduced and Cu(s) forms on the copper electrode. The diagram below depicts the anatomy of this galvanic cell.

But there’s more to this story. Let’s start with a couple of new terms - anode and cathode. The anode is the electrode upon which the oxidation occurs. The cathode is the electrode upon which the reduction occurs. (See mnemonic at the right.) In this galvanic cell, the Zn is the anode and the Cu is the cathode. As the reaction occurs, positive ions (Zn2+) are being produced at the anode. Meanwhile, positive ions are being removed at the cathode. This creates a buildup of positive charge in the anode’s half-cell and a shortage of positive charge in the cathode’s half-cell. This imbalance of charge will quickly interfere with and hinder the electron flow.

But there’s more to this story. Let’s start with a couple of new terms - anode and cathode. The anode is the electrode upon which the oxidation occurs. The cathode is the electrode upon which the reduction occurs. (See mnemonic at the right.) In this galvanic cell, the Zn is the anode and the Cu is the cathode. As the reaction occurs, positive ions (Zn2+) are being produced at the anode. Meanwhile, positive ions are being removed at the cathode. This creates a buildup of positive charge in the anode’s half-cell and a shortage of positive charge in the cathode’s half-cell. This imbalance of charge will quickly interfere with and hinder the electron flow.

A simple solution to this charge imbalance involves the use of a salt bridge (U-shaped tube) or a porous disk in a tube. The salt bridge or porous disk contains an electrolyte (such as KNO3) in a medium that prevents the actual contents from the two half-cells from mixing. The ions of the electrolyte - K+ and NO3- - are able to move from the medium into either half-cell. The flow of these ions through from the tube into the half-cell establishes electrical neutrality and ensures a sustained flow of electrons through the wire from the anode to the cathode.

The Mg-Ni2+ Cell

Magnesium metal and nickel(II) ions undergo a spontaneous redox reaction described by the following equation:

Ni2+(aq) + Mg(s) → Ni(s) + Mg2+(aq)

A galvanic cell reliant upon this reaction would include the following half-cells:

- A half-cell with a magnesium electrode immersed in a solution containing magnesium ions. Oxidation would occur in this half-cell.

- A half-cell with a nickel electrode immersed in a solution containing nickel(II) ions. Reduction would occur in this half-cell.

The two electrodes would be connected by a wire. And the two half-cell compartments would be connected by a salt bridge or a porous membrane (packed with KNO

3) in a tube to allow for ions to flow between compartments. The Mg metal is the anode. Oxidation occurs on its surface:

Mg(s) → Mg2+(aq) + 2 e-

Electrons would flow through the wire to the cathode - Ni. Reduction occurs on its surface as Ni

2+ ions gain the electrons to become Ni

(s).

2 e- + Ni2+(aq) → Ni(s)

The schematic diagram representing this galvanic cell is shown below.

Galvanic Cells With Gaseous Half-Cells

In the two examples above, each half-cell consisted of either a solid reactant or product. Thus, that solid was a useful choice for the electrode. There are however situations in which one or both half-cells consists of all gaseous and aqueous-state reactants and products. For instance, consider the following redox reaction:

2 H+(aq) + Zn(s) → H2(g) + Zn2+(aq)

One half-cell involves the

oxidation of Zn

(s). A strip of Zn would serve as the anode in this half-cell.

Zn(s) → Zn2+(aq) + 2 e-

The other half-cell involves the

reduction of H

+(aq) ions to form hydrogen gas.

2 e- + 2 H+(aq) → H2(g)

Neither the reactant nor the product is a solid. A common choice for an electrode is platinum (Pt) metal. It is a solid, a conductor, and relatively inert. Electrons move from the anode (Zn metal) through a wire to the cathode (Pt).The platinum electrode is immersed in the aqueous solution. The H

+ ions in the solution that surround the platinum are reduced. Bubbles can be seen forming on the surface of the metal. A schematic diagram is shown below.

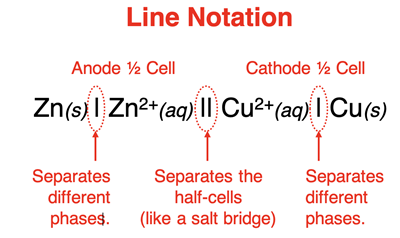

Conventions for Line Notation

In the three examples above, the galvanic cell is represented by a schematic diagram. A galvanic cell can also be represented by a so-called line notation (a.k.a., cell notation). A

line notation is a shorthand means of identifying the key components of a galvanic cell - the anode, the cathode, and the reactants and products in each half-cell. The Zn-Cu

2+ cell discussed earlier would be represented by this line notation:

Zn(s) | Zn2+(aq) || Cu2+(aq) | Cu(s)

The convention for line notation is to list the anode compartment first and the cathode compartment second. A double vertical line (||) is used to separate the two half-cells. The electrode, reactants, and products are listed for each compartment.

Species that have different phases (for example, a solid and an aqueous-state ion) are separated by a single vertical line.

Species having the same phase are separated by a comma. Ions are listed closest to the double vertical line. The initial concentration of aqueous-state ions is often included in parenthesis.

The line notations for the other galvanic cells above are:

Mg(s) | Mg2+(aq) || Ni2+(aq) | Ni(s)

Zn(s) | Zn2+(aq) || H+(aq) | H2(g) | Pt(s)

Representations of Galvanic Cells

As is evident on this page, galvanic cells can be represented in numerous ways. Some of those ways include:

- Words (which includes vocabulary terms like half-cell, half-reaction, reduction, oxidation, reducing agent, oxidizing agent, anode, cathode, salt bridge, porous disk, electron flow, etc.)

- A balanced redox equation

- Two balanced half-equations

- A schematic diagram

- Line notation

A common course goal is to be able to relate the various representations. This ability might be expressed in the following ways:

- If given a balanced redox equation, to draw the schematic diagram.

- If given the schematic diagram, to draw the line notation.

- If given the line notation, to write the two half-equations.

- If given a description of the galvanic cell in words, to draw the schematic diagram and to write the line notation.

The examples below demonstrate the ability to relate the various representations of galvanic cells. For each example, first answer the question. Then tap the

Check Answer button to assess your ability.

Example 1 - Representations of Galvanic Cells

Draw the schematic diagram for the galvanic cell based on the following redox reaction:

Pb(s) + Cl2(g) → Pb2+(aq) + 2 Cl-(aq)

Example 2 - Representations of Galvanic Cells

A galvanic cell is represented by the following line notation.

Al(s) | Al3+(aq) || Co2+(aq), Co3+(aq) | Pt(s)

Write the two half-equations and label them as oxidation and reduction. Identify the anode, the cathode, the oxidizing agent, and the reducing agent. Finally, describe the direction of electron movement between the two cells.

Example 3 - Representations of Galvanic Cells

A galvanic cell is constructed with a zinc anode and a lead cathode, with each electrode immersed in a solution of its ions - Zn

2+ and Pb

2+. Write the line notation, the balanced chemical equation for the redox reaction, and construct a schematic diagram for this galvanic cell.

Next Up

Not every reaction is

spontaneous. But there is a way to predict what reactions are

spontaneous. In

Lesson 2b, we will introduce the idea of a reduction potential. Every half-reaction can be described by a standard reduction potential that provides an indicator of the tendency of that half-reaction to occur as a reduction reaction. Understanding reduction potentials allow a student to identify which reactions are

spontaneous.

But wait! Before you navigate forward, make sure you have the ideas of this lesson understood. We have provided several suggestions for reinforcement in the Before You Leave section below. Pick one or two ideas and put your learning to practice.

Before You Leave - Practice and Reinforcement

Now that you've done the reading, take some time to strengthen your understanding and to put the ideas into practice. Here's some suggestions.

- Try our Concept Builder titled Galvanic Cells. Any one of the three activities provides a great follow-up to this lesson.

- The Check Your Understanding section below includes questions with answers and explanations. It provides a great chance to self-assess your understanding.

- Download our Study Card on Galvanic Cells. Save it to a safe location and use it as a review tool.

Check Your Understanding of Galvanic Cells

Use the following questions to assess your understanding of the various representations of galvanic cells. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

1. In a galvanic cell, electrons always flow ______.

- through the wire from the anode to the cathode.

- through the wire from the cathode to the anode.

- through the salt bridge from the anode to the cathode.

- through the salt bridge from the cathode to the anode.

2. In a galvanic cell, electrons are lost by the ______________ (reducing, oxidizing) agent on the surface of the ____________ (anode, cathode). And electrons are gained by the ______________ (reducing, oxidizing) agent on the surface of the ____________ (anode, cathode).

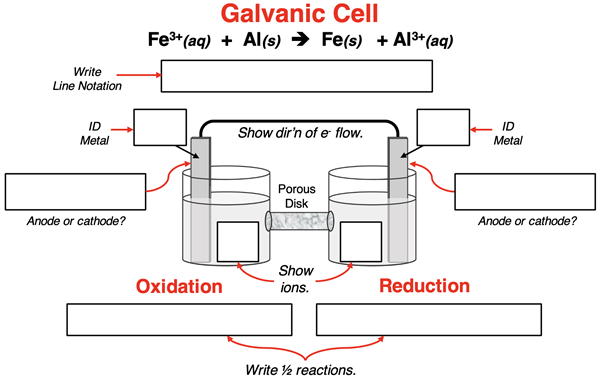

3. A galvanic cell is built to utilize the redox reaction:

Fe3+(aq) + Al(s) → Fe(s) + Al3+(aq)

Complete the schematic diagram and line notation for this galvanic cell by filling in all the boxes.

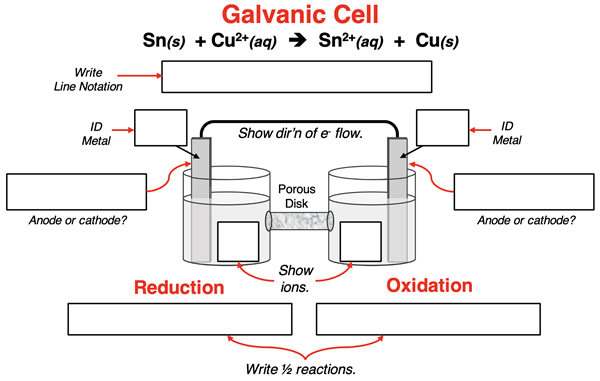

4. A galvanic cell is built to utilize the redox reaction:

Sn(s) + Cu2+(aq) → Cu(s) + Sn2+(aq)

Complete the schematic diagram and line notation for this galvanic cell by filling in all the boxes.

5. Consider the following line notation:

Zn(s) | Zn2+(aq) || Fe2+(aq), Fe3+(aq) | Pt(s)

a. The anode is ________.

b. The cathode is ________.

c. The balanced oxidation half-reaction is: ___________________________

d. The balanced reduction half-reaction is: ___________________________

e. The balanced overall reaction is: _______________________________________

6. A galvanic cell is represented by the following line notation.

Pt(s) | Sn4+(aq), Sn2+(aq) || F-(aq) | F2(g) | Pt(s)

a. The anode is ________.

b. The cathode is ________.

c. The balanced oxidation half-reaction is: ___________________________

d. The balanced reduction half-reaction is: ___________________________

e. The balanced overall reaction is: _______________________________________